By HUSSEIN ISMAIL

IN 2018, my journey with China will have been over 25 years; a long journey that started as an adventure when a friend of mine suggested in late 1991 that I go to China to work for China Today, a popular magazine covering Chinese politics, culture, education, and food.

His suggestion caught me by surprise, which is why it took me almost a whole year to think it through. I finally arrived in Beijing on September 29, 1992, after more than a 10-hour flight.

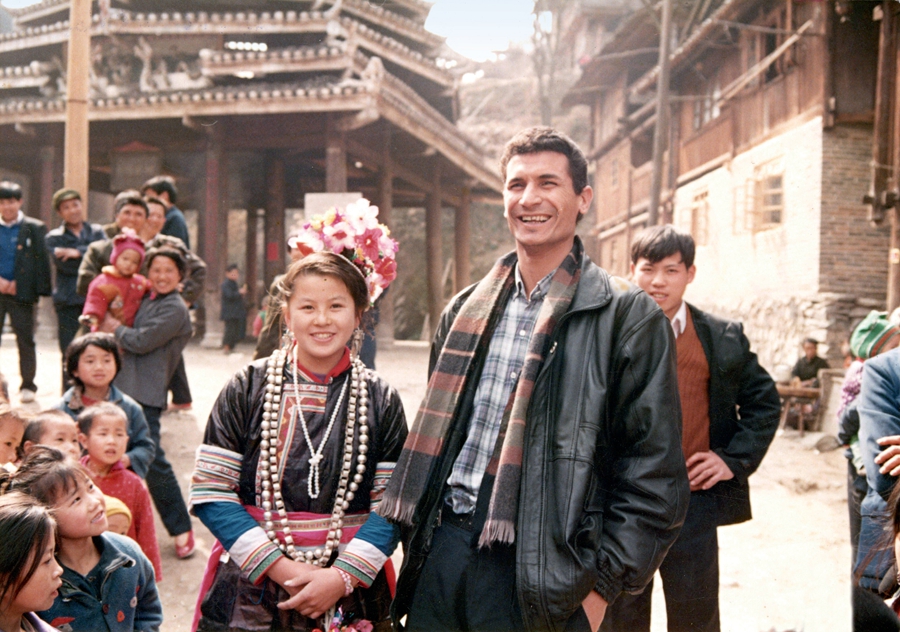

Visiting an ethnic minority group in Guizhou in 1993.

All the way up in the air, thoughts and questions flurried in my mind. For me, it was a journey into the unknown, one similar to that moment when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the surface of the moon on July 21, 1969. Whatever information I had strenuously tried to obtain about China before I arrived was not able to dispel my concerns or answer the questions sweeping my mind.

Minutes after I departed from Beijing’s Capital International Airport, which at the time was small and humbly equipped, I was in the back seat of a car driving more than 20 km before crossing a huge square, which I recognized as the famous Tian’anmen Square, the largest in the world.

Hussein being interviewed by local media in Ningxia in 2000.

While crossing the area, the distinctive red color of grand gates inlaid with large yellow shapes captured my attention, which I later came to know were the gates of the Imperial Palace in the Forbidden City, where the successive emperors of China and their entourage used to reside. The last emperor to have lived there was Puyi, who abdicated the throne on February 12, 1912 after the success of the Revolution of 1911, led by Sun Yat-sen.

A few minutes later, the car stopped, and I got out together with another guy, to oddly find myself in a Western restaurant in the capital of Communist China. After our lunch, we walked down the streets of Beijing. During our walk I noticed many beautifully arranged flower pots, the most beautiful of which being in Tian’anmen Square.

Another thing that caught my eye was the red Chinese flags hanging on shops’ doors and from people’s homes to celebrate the upcoming National Day on October 1. I enjoyed that scene, which still continues to occur for every national or traditional occasion in China.

Later I arrived at Youyi Binguan (Friendship Hotel). This was where those who were referred to in China as “foreign experts” stayed. My bag had some clothes and books inside, in addition to several nylon bags of cooked and dried food, which my mother had insisted I take. She believed I was going to a country where I might not have enough food or other necessities.

Hussein (first left) and his colleagues visit Xinjiang in 2005.

The hotel had a number of residential compounds, each with several four-story buildings surrounding a yard. Each compound had one or more gates that would close at 11 pm and open at 6 am. If you weren’t back in time, you were simply out of luck. Those who visited residents in Youyi Binguan had to register their names and information before entering, and leave before the gates were closed.

When I arrived in China at the beginning of the 1990s, it was a very delicate stage in the land of the dragon. The planned economy and ideological slogans that dominated China’s economic and political scene since 1949 had not yet waned, nor did the market economy and neorealism ideals. For those who happened to be in China during this stage, it was like someone watching a movie where scenes were moving at a rapid pace, except that it was happening in real life.

Everything suggested that the Chinese were standing on both sides of a canal; ready to cross, and hesitant at the same time, facing temptations, hopes, and new opportunities ahead, while being weighed down and pulled back by heritage and heavy thoughts.

It was a psychological, political, economic, and ideological struggle that entailed boldness as well as savvy, requiring a series of gradual steps. Some Chinese had already built up the courage at that time and decided to “go down the river of trade,” breaking the state-owned “iron pot” from which everyone must eat, drink, get dressed, take medicine, and adhere to. It was a risky adventure, but it was quite worth the sacrifice, as years later proved.

The number of foreigners in China’s capital in the early 90s was small. Mostly, foreigners, commonly known as lao wai, were treated in a special way, as people would look at them on the street, curious about them in their own way. Most Chinese people, or at least those coming from the countryside to the cities in search for a job, viewed foreigners as being “rich” and careless with how they spent money. Later, things have changed, and it is no longer surprising to see foreigners around Beijing.

For four months, Beijing had been my world. It represented China in my eyes. But Beijing is just a city, a political and cultural capital, and in no way can give a full picture of the whole 9.6 million square kilometers’ land and the entire 1.3 billion people that make up China.

With middle school students in Ningxia in 1998.

In February 1993, I made my first trip outside the capital to Guizhou Province, in southwestern China. The airport where our plane landed in Guiyang City was nothing more than an airstrip, with several offices at the end of it.

In Guizhou, I began to see another picture of China; geography, faces, livelihood, and dialects. It surprised me to see that there was someone to handle “translation” between the members of the Beijing delegation and the people of the villages and towns we visited, from the local dialect into the standard Chinese Mandarin.

The different customs, traditions, and dialects opened my eyes to a fascinating and interesting world of the ethnic minorities in China, which has 55 of them. I had seen nothing like this in Beijing, except maybe for the embroidered costumes worn by the representatives of the ethnic minorities who attended the annual “two sessions,” the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) in Beijing.

About five years after my trip to Guizhou I had another chance to engage in the world of ethnic minorities; this time being in a region that is home to around two million people of the Hui (as Chinese Muslims call themselves). Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, in northwestern part of China, had already occupied a special place in my mind before I first visited it in July 1998.

In Ningxia, I was intrigued by two things, the veiled women and the more than 6,000 minarets of over 3,000 mosques, spread in a region home to only 10 percent of China’s Muslims. On my second visit to Ningxia, two years later, I noticed the changes that had taken place, which, however, were much less than those I saw in Beijing and in the southern and eastern coasts.

The hope of visiting another region remained, until it was fulfilled many years later when I visited Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in June 2005. Visiting Xinjiang and writing about it were totally different things, as writing about this region is quite a difficult task.

What is written about Xinjiang inside China is different in one way or another from what is said about it outside China. Xinjiang offers you a unique palette of faces, terrains, languages, development, underdevelopment, richness, poverty, deserts, oases, food, and clothing. It is a vast plateau of about 1.67 million square kilometers, occupying one sixth of China’s territory, bordering eight countries along a 5,600-km line.

In this part of China, you are in a different reality. One place has two names – one in Han language and another in Uygur language. Here you see the facades of shops and government institutions and advertisements written in both Uygur and Han languages.

Over the years in China, I had learned to try to be Chinese, whether in the street, at the shopping market, in football fields, at places of worship, and while taking public transportation. I used to go to markets and into universities, where I practiced football and other sports and befriended people from different social groups. I went into cinemas, watched Chinese films, sat for a long time in front of the Peking Opera on Channel 3 of China Central Television (CCTV). I met university professors, intellectuals, and senior politicians. We talked about everything and anything, with China always being the focal point as it was the center of my interests.

When I arrived at Capital International Airport in January 2018, standing in a long queue waiting to complete the entry procedure, my memory went back to the sight of the few arrivals at the airport in 1992. On the now modern, wide highway from the airport to the city, I remembered the old narrow road, which used to be full of pits.

In front of the China International Publishing Group (CIPG) building, and in the places where I wandered, I saw nothing of the small shops and food stalls on the streets, which were now much more spacious and organized in terms of traffic movement, despite the huge increase in the number of cars.

The old bikes have almost disappeared, and been replaced by colorful shared bicycles, and public transportation has become quite convenient. Almost no public markets can be seen in the crowded center of the city, as they all have been moved to remote suburbs.

Everywhere I went, I didn’t see anyone using cash. Most financial transactions were done using a mobile application. As a Chinese friend jokingly put it, “thieves in Beijing have lost their jobs.” Everyone keeps mobile phones in their hand, as it has now become a main tool to handle their daily affairs.

I have also sensed more strict discipline. In many places, one cannot go inside unless they have their IDs or entry permits scanned on a relevant barcode. Modern technology has become an important part of the lives of individuals in China. The Chinese never stop innovating.

Once again, I realized that although I felt that I had walked down the path of Chinese society, a long path of 5,000 years of history, I am still far from claiming that I have walked the entire way. Whenever you come closer to claiming that you know much about China, you discover that you have only one step down a very long path.

When you arrive in China and experience this fascinating world, with its people, places, rituals, customs, and traditions, on your first day, you feel like you could write a book, or maybe an encyclopedia, about China. However, when one month passes, with the facts unfold in front of your eyes, the sense of humbleness, which is very characteristic of the Chinese, comes to you, you feel that now, you might only be able to write one article about this huge country.

It’s a daunting task to write about China, especially the post-reform and post-opening-up China that is changing at an amazing speed. In his diary, former U.S. President Richard Nixon said China has endless secrets. Therefore, we will not know everything about China, but perhaps we can learn something from it.

HUSSEIN ISMAIL is vice president of China Today’s Middle East Branch.