By SONG LEI

By SONG LEI

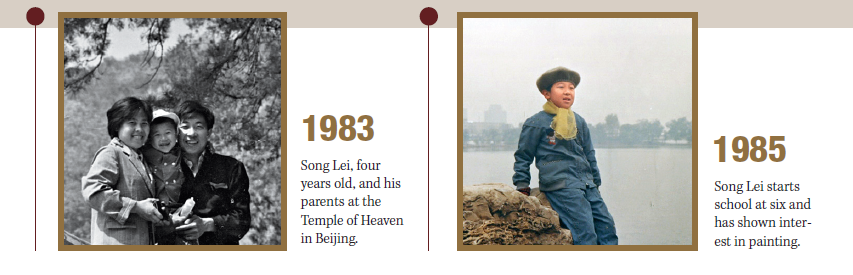

I was born into a working family in Beijing in 1979, the year after China decided to open up and reform. As a child, I loved arts, especially painting, under the influence of my mother, an aficionado of traditional arts and crafts.

From Worker to Artist

My mother, 66, has always been passionate about life. She grew up in Liulichang of downtown Beijing where for centuries many high-end painting and calligraphy studios and stores for various folk arts have congregated.

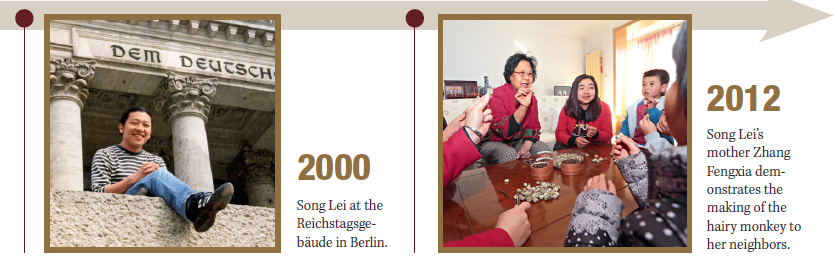

The mother and son discuss techniques of making the hairy monkey.

Like most families in the 1980s, my family was strapped for cash. However, that didn’t prevent my mother from gussying up our shabby home with whatever materials were available. In the autumn, she would put a twig with attached persimmons on our table by the window, and place a few golden fallen leaves around it. As the morning sunshine peeped in, it became a picturesque scene that warmed and lightened up our home. Our old clothes and bed sheets were all reused, and even the scrap cloth was made into collages. For all these ingenious creations, mother simply said, “I saw it in my childhood.” I had no idea what life was like when she was a girl, but it must have been different from mine.

In the late 1990s, my mother’s employer, struggling financially, allowed her to retire earlier than planned. With more free time, she took to making various handicrafts, such as the Chinese Knot, flour sculptures, and fabric collages.

On one occasion, my mother met a senior artist for making hairy monkey figurines, who complained about the generational rupture in the heritage of traditional culture. He expressed the concern of having no one to carry on his trade, as it was facing a narrow market and not bringing in a livable income, and it was struggling to appeal to young learners. Reminiscent of her early years, mother decided to learn how to make the hairy monkey figurines with this artist.

A native art of Beijing, the hairy monkey is miniature figurines made of cicada slough (for the head and limbs) and Magnolia bud (for the torso). It is named so because the figurines look like hairy monkeys. It is accompanied with props that reconstruct a scene about the life in old Beijing. My mother felt cut off from the society in her retirement and was eager to find a way to vent her emotions and communicate with the world.

Due to her experience with other handicrafts, mother made swift progress, and soon became a master in the field. She was later recognized by the municipal government as an official inheritor of the hairy monkey art.

Following the State Council’s notice on enhancing protection for cultural heritage in 2006, the Chinese government has steadily garnered support for antiqued arts and crafts. Meanwhile market demands for them have been growing, bringing those ravaged by the impact of the “cultural revolution” (1966-1976) back to life.

For a long time, many old arts and crafts faded out of public views because they were void of practical functions, and weren’t able to find buyers as most people in the country were scraping by. There were some people who partook in these cultural activities, but mainly as hobbies instead of vocations. After an increase in affluence, people in China have the money to satisfy their long-oppressed cultural needs, unleashing market demands for these arts and crafts.

My mother became busy. She was invited to cultural events organized by our neighborhood and to international exchange conventions. Many primary schools in Beijing have incorporated traditional culture into their curricula, and my mother gives a hairy monkey class once a week at a local school. Her class always fills up quickly after the application opens. She also teaches in public libraries, cultural centers, and folk art museums, and has class everyday.

From Germany to Beijing

I was born in the wake of the decade-long “cultural revolution,” which waged a war against the “Four Olds” – old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits. It eviscerated China’s traditional culture, and pushed many of Beijing’s folk arts to the verge of extinction.

I grew up in the age of reform and opening-up, when Western culture and pop music entered China and exerted tremendous influences on its youths. By contrast, the presence and influence of traditional culture were diminishing. Bric-a-bracs, things my mother’s generation played with in their childhood, such as rabbit figurine, flour sculpture, and malt candy art, were rarely seen when I was a boy.

Thanks to my mother, I fell in love with painting at a young age. After finishing middle school in 1994, I entered an art and design school in Beijing, and after graduation went on to study at a light industry college in Dalian. Two years later, I felt a strong desire to learn the advanced culture and knowledge in a developed country. It was 2000, when new media had emerged as a pillar industry in developed economies. Therefore, I decided to go study new media design in Germany. I spent the following nine years in Germany, and obtained a master’s degree.

I returned to Beijing at the end of 2009. The city was very different from nine years before. I needed some time to readjust, and see how to apply what I learned abroad locally. I first found a job with a TV advertising company, and then moved to an IT company as a user interface designer one year later. I stayed there for three years.

Many people of my generation are big dreamers but poor doers. Having learned in schools all the classics and works by luminaries in their respective fields, I felt folk arts to be unimpressive. My mother’s pursuit to make the hairy monkey was to me no more than a pastime. However, this attitude slowly changed.

In 2013, my mother’s hairy monkey mentor could not give classes any more due to health reasons, and needed someone to pick up the slack at the two schools where he taught. The time didn’t fit my mother’s schedule, so she recommended me. Now I become a freelancer giving courses on traditional arts and crafts for children. More than a decade after my 8,000-km trip to Germany, I was back at the starting point. Life has been and will continue to be unpredictable.

Aligning Traditional Culture with Modern Needs

I studied art and design in school, but all arts are interrelated. My academic background helped me learn how to make the hairy monkey, which involves multiple skills. In the learning process, I discovered a sense of fun, shared by my mother, and came to appreciate the charm of folk arts and crafts as well as the culture behind them.

In the past few years, an increasing number of primary and middle schools in China have opened courses on intangible cultural heritage. Besides my teaching activities, I founded a research team whose members are my art school friends. We designed courseware, and experimented with new ideas in teaching. I also introduced new technologies into my hairy monkey class. For instance, I developed a software using 3DMAX to display the production process of the hairy monkey on the big screen. What’s more, I led my students to place the monkey figurines in settings plucked from their lives, such as calling 119 and 110 when encountering a fire or criminals. This way, the age-old handicraft becomes educational and relevant to current times, responding to issues of concern among teachers and parents.

My team is now teaching in several primary and middle schools in Beijing. I feel very proud. For a long period in the past, craftsmen could not make a decent living, and therefore very few from the younger generation would enter the trade. Things are different now. With strong government support and solid market demands, I can sufficiently support myself by practicing a craft that I love and that introduces me to many like-minded people. It has provided me with the life I’ve always dreamed of living.

It takes passion and innovation to revive a traditional culture. My hairy monkey works are different from those of my mother as they focus more on the present, what’s happening in it, and what appeals to young people. My mother’s works are about the past, and how she remembers old Beijing.

My team and I plan to develop derivative products involving technologies that are more advanced. Though the work is still in the early stage, every new attempt and every breakthrough are heartening, and sustain our resolve to press forward on this course.

SONG LEI is a freelancer.