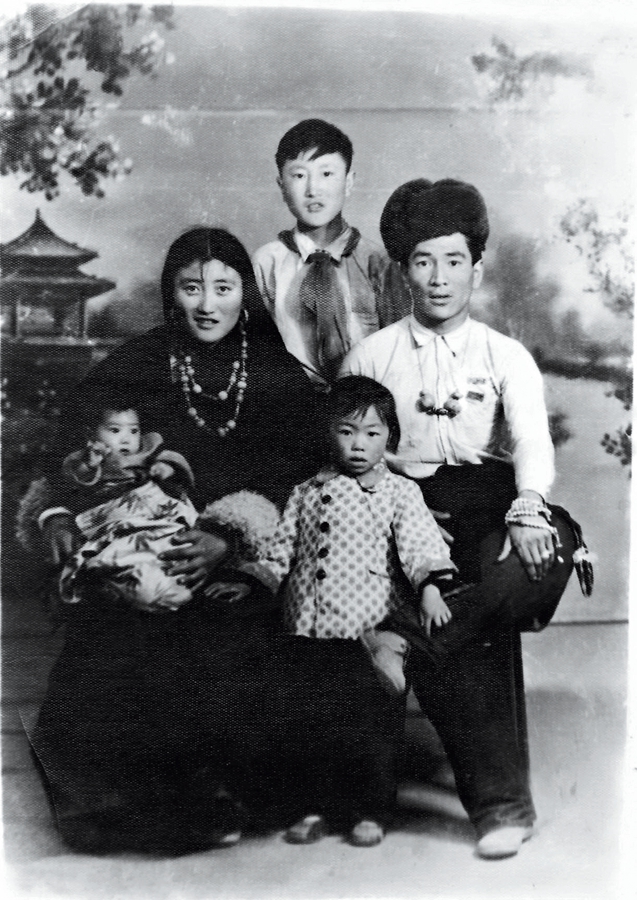

1962

AS one of the first batch of Tibetan masters students after the reform and opening-up was carried out and the first Tibetan to obtain a PhD degree in anthropology, many of my compatriots see me as the pride of the hometown. However, in reality this has bothered me for a long time because I personally think I do not have special skills or talents. I just benefited a lot from the new era characterized by the reform and opening-up.

Keeping Pace with a New Era

I was born in Garze County of Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan Province. A journalist once described me as “a Tibetologist that grew from a boy of a serfs’ family on a long and winding path. Every blade of grass in the Tibetan-inhabited region is linked to him as it is significant to his life. All the joy and pain of his life that he has experienced there sheds light into the darkest corners of his heart.”

1962

Wearing a scarf, Geleg and his sister’s family pose for a group photo in a Garze photo studio.

Before the democratic reform which was carried out in the 1950s, my parents were both serfs. At that time, we didn’t have our own house to live nor land to grow crops, so we could only survive as serfs. Since I was very young, I accompanied my sister up the mountain to let the cows graze and gather dung as fuel for the fire. We would leave early in the morning and return late at night. My mother had hoped that I would become a lama because only lamas had better prospects for the future.

In the 1950s, my hometown started a democratic reform, confiscating property from the land owners and distributing it among the poor. Our family got a new house with a glass window, a few mu of land (15 mu=1 hectare), and a couple of cows. After the peaceful liberation of Tibet, the people’s government of Tibet established the first elementary school in my village, despite the opposition of the temple and rumors of rebellion. Wanting a better future for her son, my mother took me to the new school three to four kilometers away and registered me. She hoped I would become a teacher. During my subsequent academic career, every time I encountered difficulties or setbacks, I always thought of the help and support the People’s Liberation Army gave to us. I recall the expression on my mother’s face while working her own land for the very first time after the democratic reform.

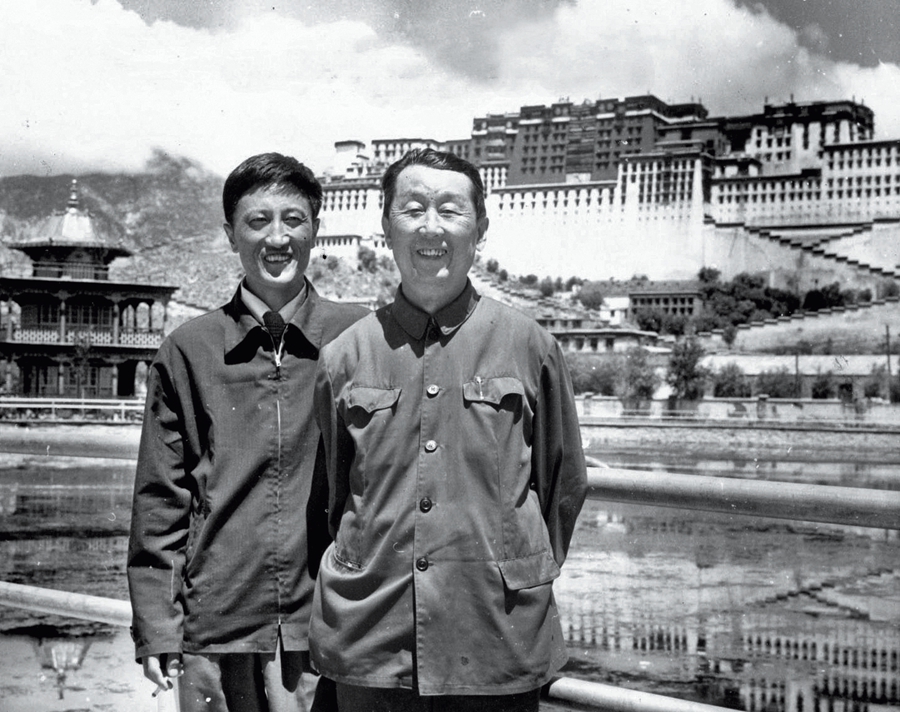

1980

Li Youyi, supervisor of Geleg’s master’s degree program, with him in Lhasa on an investigative tour.

The real change to my life came after the implementation of reform and opening-up policy. In 1977, the Chinese government reinstated the national college entrance examination system. I immediately registered and in the spring of the second year, was accepted to the Southwest Minzu University, becoming one of the first batch of undergraduate students in the Chinese language and literature department after the “cultural revolution” (1966-1976). Right after the first semester, I received news of the reinstatements of graduate programs nationwide. With the support and encouragement of my teachers and friends, I applied to study ethnic history at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS). In 1978, I came to Beijing, the capital, and entered the coveted halls of academia.

From 1983 to 1986, I studied for my doctorate at Sun Yat-sen University. This academic experience had a profound influence on my career development. Three years of strict training laid a solid foundation for my academic pursuits.

I was fortunate enough to attend two great institutions of higher learning: the graduate school at the CASS and Sun Yat-sen University. I was also fortunate enough to be guided by two excellent Han Chinese teachers: Professors Li Youyi and Liang Zhaotao.

2009

Geleg at the University of Cambridge.

As a beneficiary of reform and opening-up, systematic study made me evolve from a largely ignorant shepherd on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, dubbed as the Roof of the World, into a doctor who has made outstanding contributions to the country. In January of 1991, in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, Jiang Zemin, former general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) personally awarded me the honorary title and certificate of “Doctor with Outstanding Contributions to China.” He asked me: “Are you a Tibetan who studied anthropology?” Yes, I am a Tibetan anthropologist. I am the descendant of a family of serfs. Without the peaceful liberation and democratic reform led by the CPC, I would have at most become a lama reciting and chanting scripture and barely being able to fill my belly. There is no way I would have enjoyed the honor and esteem of being the first Tibetan PhD in anthropo-logy. It is even more unlikely that the government would have awarded me the honor and subsidy for my contribution to the development of China’s social sciences.

Witnessing Change in Tibet

Over the past 40 years, I have traveled west to Ngari Prefecture, north to the vast grasslands, south to Shannan Prefecture, and east to Qamdo Prefecture and Tibetan autonomous prefectures in Yunnan, Qinghai, and Gansu provinces. I have travelled to almost all of the towns and villages of the Tibetan-inhabited regions. I have enthusiastically unraveled the mysteries of Xiangxiong Kingdom, Guge Kingdom, and the sacred mountains and lakes. I have contemplated the human spirit, the trajectory of civilization, the meaning of life, and human suffering. I also spent much time pondering the Tibetan culture between tradition and modernity.

2012

In front of his alma mater, Garze Minzu Middle School.

However, what gave me immense pleasure and enthusiasm is the experience of conducting a number of key national projects dedicated to material and cultural progress in Tibetan-inhabited areas. These projects included the Study on Traditional Culture and Modernization of Tibetan-inhabited Areas in China, the Survey on 100 Tibetan Households, Challenges and Opportunities: Accelerating the Progress of Modernization in Tibetan-inhabited Areas, and the Study on the Strategy of Cultural Protection and Modernization in Tibet and Tibetan-inhabited Areas in Other Provinces.

For the past 40 years, one area of interest for my research has been the changes in Tibetan farmers and herdsmen who carry a long history and cultural tradition after the peaceful liberation, especially after China’s reform and opening-up. According to our field study of over 1,000 households in three different types of Tibetan regions (cities, farms, and pastures), since China started the reform and opening-up, rural and urban Tibetan societies have gone through many changes. The most obvious of which are as follows:

After the reform and opening-up policy was carried out, the household contract responsibility system was implemented in the rural areas of Tibet. The right to use land and possess livestock has been transferred from collective organizations to individual farmers and herdsmen. This linked their initiative over the management of production directly to their respective interests. It therefore promoted the development of productivity, increased the income of farmers and herders, and significantly improved their living standard.

After the reform and opening-up was carried out, Tibet’s agricultural and pastoral areas have gradually seen a change from a unitary, self-sufficient economy to an open and diversified commodity-based economy. No longer limited to growing crops and raising livestock, farmers and herdsmen began to take advantage of the opportunities offered by the open markets and improved transportation, engaging in industry, architecture, transportation and shipping, business, and the catering industry.

On a tour of investigation in Lhasa in 1993.

Along with economic development and the improvement in people’s lives, both city dwellers and rural farmers are experiencing a shift in their lives from earning just enough for subsistence to having more money for consumption. Moreover, the consumption is increasingly leaning towards technology, education, tourism, and entertainment. Modern appliances like televisions, washing machines, VCRs, cars, motorcycles, cellphones, cameras, and microwave ovens, have all made their way into Tibetan households, gradually from urban to rural, after the reform and opening-up was implemented.

After the reform and opening-up, the normal religious activities of Buddhist worship are protected and respected under state policies. The Tibetan people have restored their right to freedom of religious belief to the fullest. According to a survey, the Tibetan people are highly aware of the policy of freedom of religious belief and it is among the best understood policies by the Tibetan people. It is widely believed to be a very good policy. In traditional Tibetan society, becoming a monk was believed to be one of the best occupations for young men. After decades of reform and opening-up, now over 60 percent of parents hope that their children can become doctors and government staff. This does not mean that they do not believe in Buddhism, rather their ideas of employment have clearly changed.

In terms of housing, the basic residential necessities of rural farmers and city dwellers have been adequately met. The average per capita housing space is 2.6 times the size it was before the democratic reform. Now the people aspire to renovate their old houses and move into newly-built multi-story apartments. Many new homes are even more beautiful and lavish than the estates of the pre-liberation aristocracy.

In terms of food, both urban and rural residents have all transformed from having a subsistence diet to eating well. Although the demand for traditional staple foods, raw grains, and coarse grains is still very large, it has shown a downward trend. This is evidence that the dietary standard has gradually increased.

In terms of clothing, the demands of Tibetan farmers, herdsmen, and urban residents are no longer satisfied with merely keeping warm. Instead, they seek more variety and style, driving a demand for medium- and high-end apparel. For example, there are more and more people wearing suits in Lhasa.

In terms of political life: after the reform and opening-up kicked off, democratic elections at the community level have become an important way for Tibetans to participate in political management. The selection of the members of the new administrative organizations is based on their talents and social achievements, replacing tribal or family style elections in the past.

Introducing the Real Tibet to the World

As an anthropologist, I often receive invitations to attend academic conferences and meetings abroad. I see them as a great opportunity to introduce the real Tibet to the world.

In 1989, I delivered a speech to over 80 American scholars at the Pacific Lutheran University on the topic: “Is Tibet the Shangri-La or a feudal serfdom society?” At the University of California, I lectured to more than 60 American students that China is a big family of 56 ethnic groups. I explained Karl Marx’s theory of ethnic studies, as well as ethnic regional autonomy, and national unity. Through these types of unofficial and non-governmental cultural exchanges, young Americans have learned about the reality of ethnic minorities in China, including of course the reality of Tibet.

Over the past 40 years, I have travelled half the world, finding that scholars of Western countries exhibit a clear ambivalence: they naturally live in modern societies, but once they discuss the modernization of Tibet, they tend to make accusations and cause constant controversy. To many Westerners, Tibet is an exotic myth, especially after the publication of Lost Horizon in 1933, in which the “search for Shangri-La” seduced the world. They imagine Tibet as the spiritual home and refuge as people have dreamed about.

As a Chinese Tibetologist, my material dream is to realize the economic modernization of Tibet, and my spiritual dream is to see the Tibetans, together with people of other ethnic groups in China, enter the new era of socialism with Chinese characteristics.

Now that I am almost in my 70s, I am happy to have continued teaching and conducting scientific research, making my contribution to the cultivation of talents in Tibetology and anthropology, the development of Tibet, and safeguarding the country’s territorial integrity and national unity. This has also been my life-long ambition.

GELEG, born in 1950, used to be vice secretary general and researcher of China Tibetology Research Center, and now is a doctoral supervisor in ethnic studies and Tibetology at Minzu University of China and Southwest Minzu University.