IN the early years of the People’s Republic of China, China’s medical virology research was still in its infancy. Some viral diseases, such as measles, poliomyelitis, and epidemic encephalitis B posed serious threats to people’s health and lives. In this regard, the Chinese government attached great importance to dealing with the situation and made great efforts to train professionals in virology research to tackle key scientific and technological problems for the diagnosis, prevention, and control of epidemic viruses.

Hou Yunde is one of them. For more than 60 years in his life, he has been fighting various kinds of vicious viruses, and he is considered the founder of molecular virology and genetic engineering in China.

Resolve to Learn Medicine and Conquer Sendai Virus

Hou Yunde was born in Changzhou, Jiangsu Province in 1929. At a young age, he had the ambition to study medicine and become a talented doctor as he watched his elder brother die of an infectious disease but was helpless to prevent the tragedy. In 1948, with excellent test scores, he was admitted to the School of Medicine in Tongji University.

The First Symposium of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention is held May 13-14, 2009, in Beijing, where academician Hou Yunde presents a report on the characteristics of virus infection and its prevention and control measures.

In 1958, Hou was sent by the government to study at the Ivanovsky Institute of Virology, Academy of Medical Sciences of the former Soviet Union for an associate doctorate degree in parainfluenza virus research. At that time, virology was an international frontier subject, and China’s research in this area was very weak. During the three and a half years of studying abroad, Hou devoted himself to research. The office hours at the institute ended at 4:30 p.m., but he continued to study in the laboratory and library until midnight, becoming the last person to get off work in the institute. The guard there was moved by his diligence and gave him a key to the lab, making a rare exception for him.

One day, the institute was thrown into disarray as all the mice there died at once. The symptoms looked strange and the virus was unknown, which made the Soviet experts feel at a loss. Hou attempted to figure out what had happened. After investigation, he noticed that the characteristics of infection and death of the mice coincided with the Sendai virus, a rare pathogen. He used a sample from a mouse, and repeated experiments until he eventually isolated the virus in the laboratory. “How could a new student from China have such ability!” was the reaction as Hou’s discovery amazed the whole institute.

The symptoms of the mice made him suspect that the Sendai virus was also pathogenic to humans. He tracked down by following clues and finally found two varieties of the virus, confirming his speculation. In 1961, he was also the first to discover that the Sendai virus could fuse monolayer cells, and became one of the earliest scientists in the world to discover cell fusion. The discovery also indirectly promoted the birth of the monoclonal antibody technology in the world. Around these findings, Hou published 17 papers during his study in the Soviet Union.

In recognition of his outstanding performance, the Soviet Ministry of Higher Education in 1962 directly awarded Hou a PhD in Medical Science. This was an unprecedented occurrence in the decades old history of the institute.

At the banquet celebrating Hou’s doctoral degree, the institute director urged him to stay, but he chose to return to China.

China’s First Genetically Engineered Drug

In 1962, Hou returned to China, and immediately engaged himself in research on medical virology. He began studying the etiology of respiratory viral infections to identify and isolate main pathogens of respiratory diseases. In little more than a year, three types of parainfluenza viruses, type I, II and IV, were isolated, which explained the major viruses causing respiratory disease epidemic outbreaks in Beijing from 1962 to 1964.

Hou Yunde’s laboratory guidance experiment in the 1990s.

In the early 1970s, Hou found that Astragalus can induce the human body to produce a broad-spectrum antiviral substance, interferon. This glycoprotein, which was discovered by foreign scientists in the 1950s, had already been made into antiviral drugs, but the import price was high and availability extremely scarce.

At first, Hou chose to induce the white cells contained in human umbilical cord blood to produce interferon. However, 8,000 milliliters of human blood can produce only one milligram of interferon. This means the cost to produce one dose (1/250mg) of interferon would cost more than RMB 100 at that time. How could such a drug be mass-produced in a country with a billion people?

Being at a loss as what to do, in 1977, the genetic engineering of human growth hormone release inhibitors was declared successful in the U.S. The news stirred the world as well as Hou. He boldly envisaged utilizing advances in genetic engineering to allow bacteria to produce interferon in large quantities.

In 1979, genetic engineering was something unheard of by most Chinese, not to mention biotechnology. Interferon production by genetic engineering requires oocytes from Xenopus laevis, but where to find Xenopus laevis? Hou was reluctant to give up. He made various attempts, and eventually at a farm in the suburbs of Beijing, he found an African Crucian carp whose oocyte became an ideal substitute. In that year, his method for the preparation of interferon debuted at the International Conference on Interferon held in New York, and immediately won acclaim from international specialists for being simple to operate.

He also successfully developed the recombinant interferon a1b, China’s class I drug product. It is clinically proven to have obvious curative effects on hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and hairy cell leukemia, and its side effects are much less intense than those of similar products abroad. This is the first drug produced by genetic engineering in China, filling the gap in this regard.

Over the following 10 years, Hou led his team to develop eight kinds of gene drugs using gene technology, and all of them have been commercialized. Now more than 90 percent of interferon drugs in China are produced domestically; tens of millions of doses of a1b interferon have been consumed nationwide for the treatment of millions of chronic hepatitis B patients and children with respiratory infectious diseases. Through export it also generates hundreds of millions of yuan for the country every year.

Establishment of Infectious Disease Prevention and Control System

In 2008, 79-year-old Hou was appointed by the State Council as the Technical Director of the National Science and Technology Project for the Prevention and Treatment of AIDS, Viral Hepatitis and Other Infectious Diseases. He led the top-level expert group in designing a general plan for reducing the morbidity and mortality of AIDS, tuberculosis, and viral hepatitis as well as for responding to major epidemic outbreaks from 2008 to 2020. He put forward the idea of an “integrated” prevention and control system for dealing with acute infectious diseases, which is to integrate various technologies to deal with emerging outbreaks, establish joint prevention and control mechanisms, and integrate all forces to deal with the epidemic.

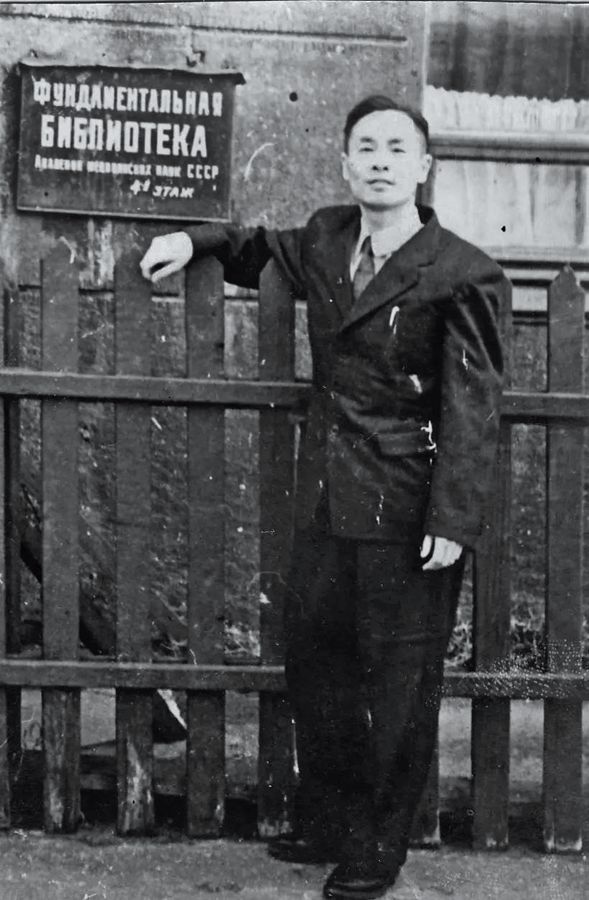

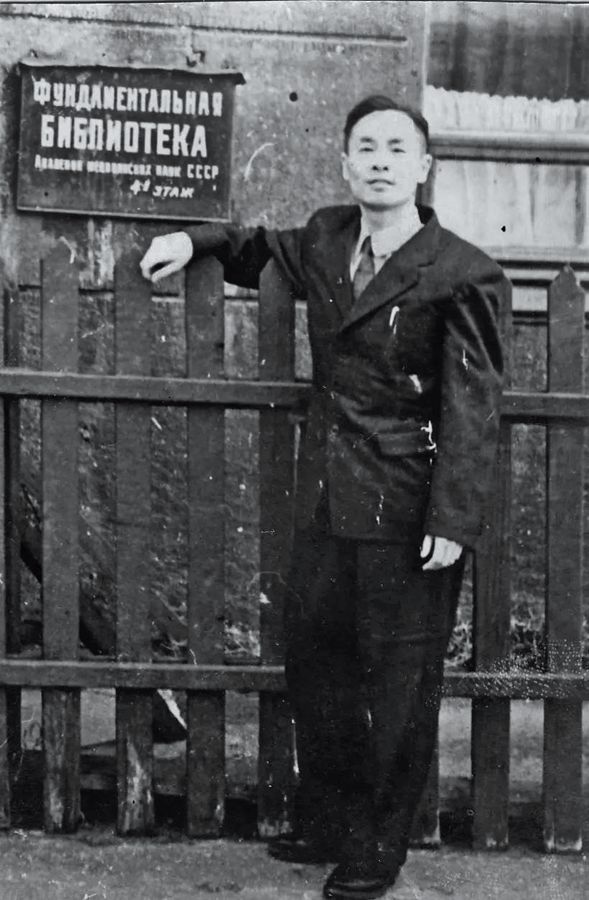

Hou Yunde during study in the Soviet Union.

The network enables rapid identification of more than 300 pathogens in five syndrome groups within 72 hours, and has a technical system ready for detection and identification of unknown pathogens, greatly improving China’s capability to prevent and control new outbreaks of infectious diseases.

In March 2009, H1N1 flu broke out in Mexico and the U.S. Three months later, the WHO raised the alert level of H1N1 virus to phase 6, indicative of a global influenza pandemic. At that time, it was a new infectious disease, without diagnostic regents and vaccines.

Hou and his research team, within 72 hours after the acquisition of influenza virus strains, established a rapid and sensitive H1N1 virus detection method after screening over 1,000 times, and verifying cross-reactions with 17 different influenza virus subtypes. Moreover, just 87 days after the H1N1 outbreak, China successfully developed the H1N1 vaccine, becoming the first country in the world to approve the release of H1N1 vaccine on the market, several months ahead of Europe and the U.S.

After the introduction of the pandemic influenza vaccine, China quickly established the world’s largest database for monitoring adverse reactions of vaccine cases (70 million cases) to provide a safety basis for global influenza vaccination.

In 2013, China first discovered that H7N9 avian influenza virus can infect human beings. Its infection rate is 100 times higher than that of H5N1, and the mortality rate is 40 percent. It took less than a month for the new virus to be discovered and controlled.

In 2014, the Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome spread to the world again. An infected South Korean was quickly detected by the network after he entered China and was diagnosed and quarantined locally. There was no domestic case reported in China.

Because of his outstanding achievements in virology, Hou, at the age of 89, won China’s top science award for the year 2017, the State Preeminent Science and Technology Award, on January 8, 2018.

“The purpose of knowing the world is to transform the world.” This is Hou’s favorite saying. Looking at his life, it is a process of constantly knowing viruses and fighting them. During this process, he has experienced numerous setbacks and failures, but never gave up his ideal, and has made outstanding contributions to the cause of disease prevention and control in China.