THE Yellow River is the second longest river in China and called the cradle of Chinese civilization. With a drainage area totaling 750,000 square kilometers, it runs 5,464 kilometers through nine provinces and autonomous regions before emptying into the Bohai Sea.

Beginning in the eighth century, soil erosion in the upper and middle reaches of the river caused a higher accumulation of silt in the lower reaches, leading to frequent flooding and changes of the river course in the lower reaches. Over the past 2,000 years, according to written records, there were more than 1,500 incidents of flooding and 26 river diversions in the lower reaches of the Yellow River, each leaving tens of thousands of people homeless. As a result, rulers in ancient times paid great attention to harnessing the Yellow River. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, several projects were carried out to try and reinforce the levees along the river. But despite much efforts, floods remained a threat to people living in the river regions, especially in the middle and lower reaches. On several occasions the river overflowed its banks, causing severe losses.

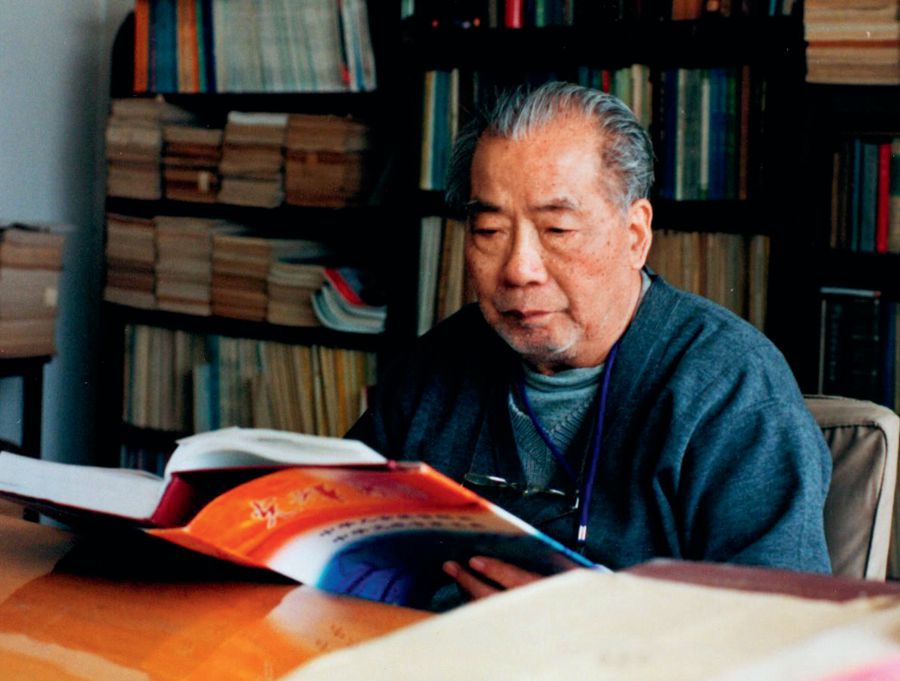

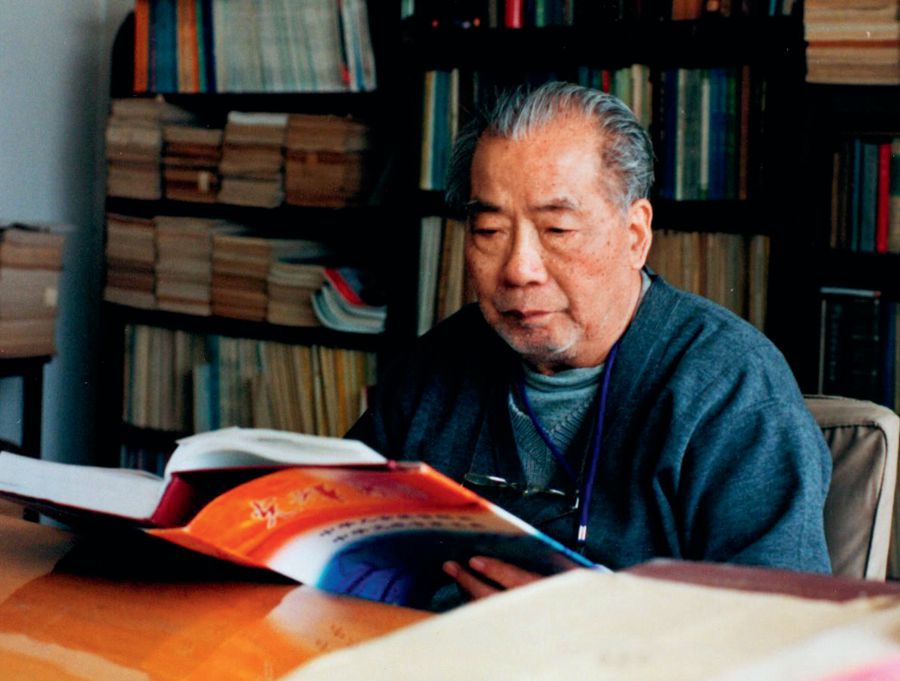

Zhu Xianmo (1915-2017), a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), pedologist and expert of water and soil preservation.

For many generations, Chinese scientists have worked hard to maintain flood control of the Yellow River by reducing the silt in it. Zhu Xianmo, a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), a pedologist, and expert of water and soil preservation, was just one of them.

From Big City to the Loess Plateau

Zhu (1915-2017) grew up in a rural area of Shanghai, and began to work in the fields at an early age. Later he enrolled in the agricultural chemistry department at the National Central University, and majored in fertilization. After graduation, he joined the Beibei Central Geological Survey Institute in Chongqing, and worked under the renowned pedologist, Hou Guangjiong. This tutelage changed his life forever.

In the early years of the PRC, Zhu worked at CAS Institute of Soil Science in Nanjing. Then in 1959, answering a call to help develop then underdeveloped Northwest China, he volunteered to move to CAS Institute of Biology and Soil Science (now CAS Institute of Soil and Water Conservation) in Shaanxi Province, and worked there studying loess for the rest of his life.

Shaanxi at that time had a dire shortage of basic daily life necessities and had poor public services including medical care. Despite these facts, Zhu worked as diligently as he could, and after extensive field study in regions at the middle reaches of the Yellow River, he proposed to build a soil erosion observation station in the Ziwuling Mountain on the border between Shaanxi and Gansu provinces. He chose this region because local vegetation recovered on its own after destruction by wars during the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1911), making it an ideal subject for studying the evolution and rehabilitation of vegetation and soil erosion on the loess plateau. This kind of study, Zhu believed, would lead to finding a solution to water and soil loss on the plateau, flooding of the Yellow River, and accumulation of silt in the Sanmenxia Reservoir.

Ziwuling was a forlorn, inaccessible region at the time, but Zhu was undaunted. He led a team of 30 people to conduct many experiments there, and talked with farmers to learn how they adapted to local conditions. Over the span of half a century, Zhu made two dozen trips across the loess plateau and beyond – crossed the Kunlun Mountains three times and traveled into Xinjiang twice.

The 28-Chinese Character Strategy

Based on his extended field study and vast research of over 40 years, Zhu put forward a “28-Chinese Character Strategy” for water and soil preservation on the loess plateau, proposing to retain rainwater in the soil and grow different plants on different terrains.

The Yellow River runs 5,464 kilometers through nine provinces and autonomous regions.

In Zhu’s observation, the reason for soil losses on the loess plateau was that the intensity of rainfall exceeded the water penetrability of local soil. To solve this problem, water penetrability of soil needed to be increased so that all precipitation could be retained locally. Different plants needed varying amounts of water to grow; therefore they should be grown on land of different topography. Zhu suggested to grow grain crops on flat plots, which can easily retain rainwater and therefore guarantee high yields, plant fruit trees in valleys or other places adjacent to water resources, and cover steep slopes with grass to prevent mudslides.

This strategy proved to be effective after its application in the regions along the Wuding and Huangpu-chuan rivers and 11 pilot areas on the loess plateau during the Seventh and Eighth Five-Year Plan periods (1986-1995). In 1997, then Vice Premier Jiang Chunyun met with Zhu and heard his report on the “28-Chinese Character Strategy.” Impressed by it, he then gave instructions as to how to expand its application.

Over the following years, Zhu continued to present new ideas on water and soil preservation on the loess plateau. He told himself that he could not die in peace until the muddy water in the Yellow River had turned clear. At the age of 91, he published a thesis in the Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences about harmony between man and nature on the loess plateau.

Thanks to such environmental preservation programs like the Grain for Green Project, by 2015, the formerly drab loess plateau was largely covered in green, and the annual volume of mud and sand carried away by the Yellow River had reduced from 1.3 billion tons to 300 million tons, far below the river’s equilibrium ratio of 800 million tons. In this sense, the Yellow River was clear.

A 2017 survey found that in non-flood seasons, water in more than 80 percent of the segments of the Yellow River was clear. In May that year, every cubic meter of its water contained less than 0.8 kg of sand. This news greatly delighted Zhu, he said, “Since the Yellow River is clear now, I can leave the world without regret.” Soon after that, he passed away in October of the same year at the age of 102.

Independent Thinking and Selfless Devotion

Zhu was an independent and critical thinker, who never readily accept the views of others or the accepted theories found in textbooks without research. As early as 1948, he put forward an unorthodox theory about the red soil in Jiangxi Province, which immediately met with incredibility in the circle of soil science. But he stood by it until it was corroborated by the study of CAS Institute of Soil Science 40 years later.

Born and raised in the countryside, Zhu felt a strong bond with soil and farmers, which inspired him to work on the barren loess plateau for more than 50 years and contribute to the nation unselfishly. When he and his family first came to Shaanxi, they lived in a small one-story house without kitchen, toilet, tap water, or electricity. He studied first by candle light and later kerosene lamps, and had to put his books, papers, and soil samples in the doorway. Despite his harsh environment, he never complained about his living or working conditions.

“For the need of the country, Mr. Zhu moved his family to the desolate town of Yangling in Wugong County, Shaanxi Province, and dedicated himself to the study of soil on the loess plateau. As a young man, I was deeply moved by his devotion, and was confident that I, who also worked in Yangling, could make internationally recognized achievements in scientific research too,” recalled Li Zhensheng, an academician of CAS and 2006 winner of China’s highest sci & tech award. It was the dedication of Zhu Xianmo, Li Zhensheng, and other scientists like them that has made it possible for China to come as far as it has today.