When the General Assembly of the United Nations passed a resolution that recognized the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as the only legitimate representative of China on October 25, 1971, I was a middle-school student in a mountainous village in southern China. Although excited on hearing the news on the radio, I knew little about the world body. But as fate would have it, I joined the government department responsible for the country’s external economic relations upon university graduation in 1978. For the third-odd years that followed, I observed in close range what the role China played in the UN and how its role evolved as the country itself was undergoing a major transformation.

The resumption of China’s legitimate seat at the UN has undoubtedly changed the political landscape in the world body. For the first time in the UN’s history, developing countries had one of their own in the top decision-making body for world security. Prior to China’s return, the Security Council of the UN was divided along the ideological line. In their consumption with getting an upper hand over the other side, both camps often ignored the concerns and aspirations of developing countries. Developing countries badly needed a champion for their cause, and they now finally found one in China.

Since the fateful day when developing countries, as Chinese leaders affectionately described it, carried the country over their shoulders into the UN, China has sided with the developing world. China identifies itself with developing countries, vowing that the one vote China has would always belong to developing countries. It has worked closely with other developing countries in such alliances as the Group of 77 and China to establish a united front, and has shown its readiness to fight for their cause. Among the 29 vetoes it used over the past five decades, 19 were over the candidate from Austria as the Secretary General of the UN, who was competing against the candidate favored by developing countries. Another six were targeted at draft resolutions mostly by the US and the UK against developing countries such as Burma, Zimbabwe and Syria, moves that China saw meddling into the domestic affairs of other member states.

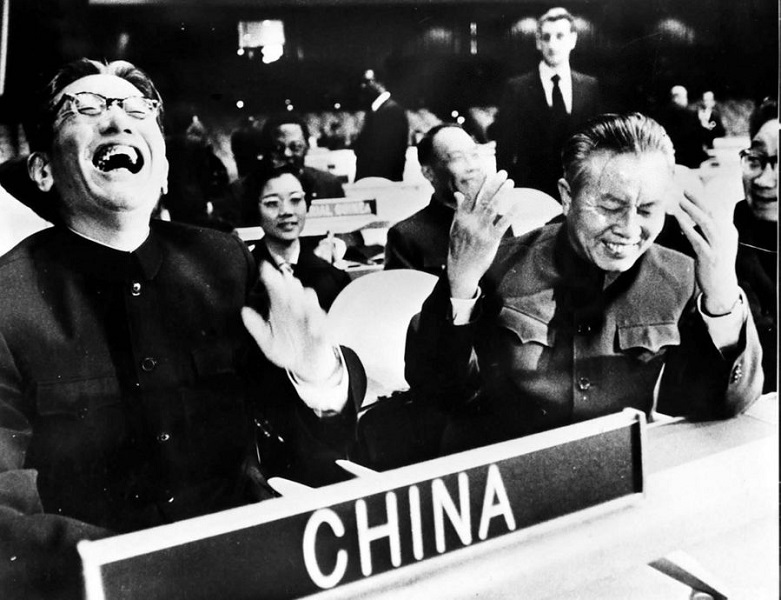

File Photo shows Qiao Guanhua (L, front), then vice foreign minister of the People’s Republic of China, and Huang Hua, then Chinese representative to the UN, reacting at the 26th United Nations General Assembly on Nov. 15, 1971. (Photo/Xinhua)

After an initial period of observing and learning, China turned into an active and indispensable participant in the UN and all its 17 specialized agencies, contributing its wisdom and resources to the missions of the organizations. As UN Secretary-General António Guterres put it, only with the support of China, was the UN better able to do its job. China accounts for over 9 percent of the budget of the UN, which makes the country the second-largest contributor to the UN coffers. And four Chinese nationals currently head UN specialized agencies.

In peacekeeping, since 1989, China has taken part in 30 UN’s peacekeeping operations, with over 48,000 Chinese officers and soldiers and more than 2,600 police serving in strife-stricken countries. It is ironic that while the Chinese soldiers were risking their lives for the peace and safety of the local people, US troops were bringing upheavals and misery to countries such as Afghanistan and Libya.

In climate change, China is a driving force for the UN’s mitigation action. It was instrumental in concluding the Paris Climate Accords in 2015. It is now leading the world in its zero-carbon drive. Its pledge to reach a carbon peak by 2030 and become carbon neutral by 2060 is nothing but ambitious. It means that China plans to achieve zero-emission in 30 years from peaking greenhouse emission, compared with the EU’s 70 years and 40 years for both the US and Japan. Commentators point out that the goal requires the country to reduce carbon dioxide emission by 317 million tons a year, twice as much as the amount for the US, and 3.5 and 9 times the EU and Japan respectively.

A Chinese peacekeeper explains drug descriptions for local people in Beirut, Lebanon, Aug. 19, 2018. (Photo/Xinhua)

The last five decades have also seen China playing an increasingly important role in the UN’s effort in promoting global development. When China was first back at the UN table, it focused on sharing its experience and technical expertise. Centers on appropriate technology such as aquaculture, small hydro and biogas were set up in the country to provide training and technical services. However, while continuing its technological transfer to other developing countries., China placed itself at the receiving end of technical assistance from the UN in 1978.

I personally participated in the discussions with the UN’s first China mission on projects to be funded by the United Nations Development Programme. As it developed, China became a net aid provider, and began to share more and more of its resources with other developing countries. While China’s efforts at helping other countries continue to be largely channeled through bilateral programmes and other multilateral mechanisms it led in setting up such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, New Development Bank and the Belt and Road Initiative, it has boosted south-south cooperation through the UN.

For example, as part of its efforts to contribute to the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, it created a special fund for south-south cooperation in 2015. And in the same year, China founded an institute associated with Peking University, a world top-ranking university, exclusively aimed at exchanging experience in national development and training high-caliber academics and government officials for other developing countries.

Apparently, China in the UN over the past 50 years has proven to be an agent for change for the better for the world, as both a promoter of world peace and a contributor to global development. However, its job in the world body is far from done.

Workers transport a second batch of vaccines developed by Chinese pharmaceutical firm Sinopharm at an airport in the central Bolivian city of Cochabamba on March 30 to advance the country’s mass immunization campaign against COVID-19. (Photo/Xinhua)

To start with, the international order with the UN at the core and the fundamental rules governing international relations based on the Charter of the United Nations are now under threat. In a bid to remold the world body in its own image, the West seeks to replace them with its own rules. If such an effort were to succeed, much of the gains that developing countries have made over the past decades would be burnt in flames, and the UN would be in jeopardy. Thanks in part to the UN, a third world war has been avoided so far, but its menace has yet to disappear, and new regional wars lurk. US President Joe Biden has recently declared an end to US large-scale military interventions, but it is doubtful that his promise would be honored by his successor. Habits, harmful ones, in particular, die hard. There is no possibility that the US could reframe from using military force in the name of democracy or human rights. At the same time, civil strife and terrorism will continue to plague parts of the world. Maintaining peace in the world is pressing as ever for the UN.

Another major challenge for the UN is to address the lack of development in poor countries. Despite an exponential increase in wealth on earth, hundreds of millions of people continue to suffer from hunger and illiteracy. Covid-19 has worsened the unbalanced development globally. The UN would be in danger of missing its goal that no one is left behind if it fails to mobilize all global resources.

In its drive to build a shared future for humanity, China sees the concerns of the world as its own. Going forward, China is expected to work closely with the UN in addressing the challenges that mankind faces, contributing more of its wisdom and resources to the realization of its common aspirations. China’s role in the UN in the next five decades looks to be even more constructive and transformative. Let’s look forward to it.

Zhou Xiaoming is Senior fellow at China Center for Globalization, Former Deputy Permanent Representative of China’s Mission to the UN Office in Geneva.