A recent online discussion by an American who had lived in China for some years made some good points about what was likely to constitute someone who would have a sensible take on the country.

Knowledge of its history was important, rather than just knowing about things that were happening now, they said. So too was having lived experience of the country, rather than brief visits. Some facility in speaking and reading the country’s language was crucial too. It was important also to understand that for all the complexity and enormousness of China, in the end it was a story of many individual people. Getting some way of grasping that is important.

Finally, on top of all of this, was a sense at least of empathy and emotional understanding. China and its culture and national narrative might be different — and in some places hard to understand for those outside its traditions. But making quick judgements in this sort of context is rarely a good idea. One had to, first of all, do one’s best to understand before firing off judgements and evaluations.

One of the complaints I have encountered when thinking and speaking about China in the last two years in particular has been that the sort of ‘nuance’ acquired through this process of thinking and evaluating is sometimes not regarded as a good thing. In response to one piece, I had co-written about China and Australia, a think tanker working in Melbourne issued a sharp denunciation, saying that the line I had taken with my co-author was too nuanced! This is something that I have found bewildering ever since. If you are faced with a situation that you have to honestly record as being not straightforward, and involving many different elements, then surely to deny this is simply being dishonest. Was dishonesty and oversimplification really what this critic was supporting? What is the problem of nuance when that is the only posture that can sensibly be taken?

A recovered patient (R) waves to medical staff of the temporary hospital, which applies traditional Chinese medicine treatment to patients, in Wuhan. (Photo/Xinhua)

This issue has been compounded by a phenomenon I have noticed as the pandemic spread over 2020. This has meant that issues about China and responses to China’s role in COVID-19 have provoked a far wider field of people to talk about, and take interest in giving opinions on the country. In principle, it is a good thing that more people are engaged in working out how to live in a world where China has a larger role. There has been too much complacency in Europe and America for too long about just assuming that the current global order will, and must, prevail for ever. It is clearly crucial to recognise that change is happening and work out how best to respond to this. Even so, the divisiveness of social media discourse has meant a complex situation, involving complex arguments that can simply not be put in a Tweet of 240 characters, has become distorted and simplified almost to the point of being meaningless.

After this experience, in late 2021, I can safely conclude that whole having an opinion about China in the West today is very common, having knowledge is something different. What is striking is that there are few who are willing to at least acknowledge what they don’t know and simply go on the power of their opinion and emotions. Like most people, I have opinions about, for instance, the US and its current politics. But I’m also very aware that there are massive amounts about the governance system of America, its society, the difference between different states, and how the federal system works, that I don’t know. Even doing a bit of research on this area exposes more things I am lamentably ill-informed about.

The first batch of Chinese COVID-19 vaccines arrived at Tashkent International Airport in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, on Mar. 27, 2021. (Photo/Xinhua)

It is fascinating therefore to come across individuals now opining on China in the public sphere in, for instance, the UK where to not know about China is almost regarded as a badge of honour. One energetic lobbyist when recently interviewed about their personal engagement with the country stated that, despite having well ventilated views about the place, they had never visited it. Nor, it was clear, did they display the smallest smidgin of basic knowledge about its recent or deeper history. They spoke not a word of Chinese. They had clearly never tried to systematically research or study any aspect of the country. But, they proudly declared in the interview where they were surrendering yet more opinions about this place they had no direct experience of that sounded cast iron and utterly certain, all of this was permissible because they ‘loved the Chinese people’ and wanted to help. That validated their ignorance, at least in their own eyes.

Perhaps one immediate way they could be of service to Chinese people (whatever such a grand and generic term might mean) would be to know a little about what they were purporting to talk about. After all, there is no lack of good books on China, and plenty of good quality courses and online material. But it’s unlikely when someone is investing so heavily in their prejudices and preconceived opinions that there would be any attempt to allow space for complexity, doubt and uncertainty in all of this.

For me, acknowledging and managing uncertainty and doubt about a subject as enormous as China is crucial. Yes, in the end the term just denotes a geographical space. At the most basic level, China is a country, with borders, delineated territory, and a physical reality. But beyond this, it is also a hugely diverse community which lives within that space. The diversity does not cut in easy ways. It involves ethnicity, socio-economic groups, and different kinds of cultural and religious actors. With provinces, prefectures, counties, down to townships, and to villages, China is multi-layered. In my years of living in and visiting the country, I have grown a bit familiar with a few places.

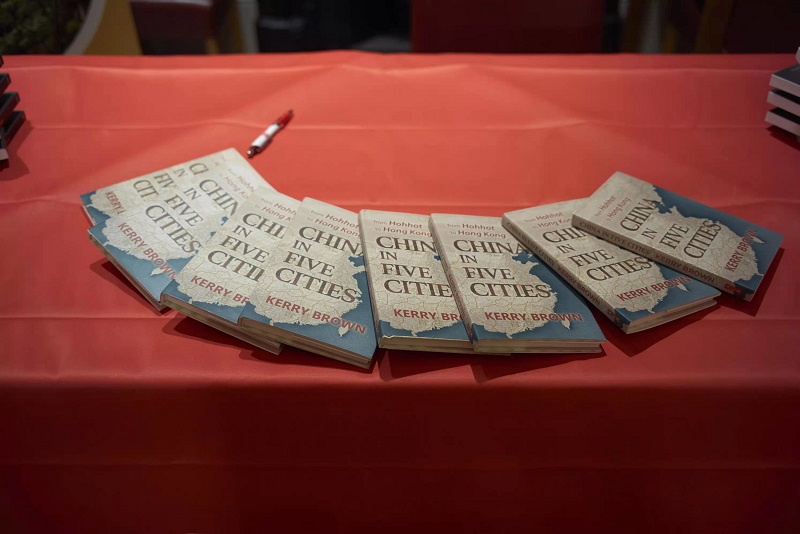

Kerry Brown’s latest book, “China in Five Cities” – from Hohhot to Hong Kong (Photo/Lau China Institute/King’s College London)

In 2021, a book about the Chinese cities I know best and have the most experience of will be published. China in Five Cities recounts my experiences of Hohhot in Inner Mongolia where I lived in the mid-1990s, Beijing where I lived from 2000 to 2003, Xi’an which I visited over 50 times from 2001, Hong Kong and Shanghai. All of these places are very different from each other. And yet they are all distinctly ‘Chinese’. Working out how the ‘language game’ of China works across these great differences, while still at least allowing for some recognition of an underlying linked similarity, has proved a lifelong process for me. For each of even these places, even when I go back, I am struck by not just their familiarity, but their newness. China is ancient, for sure — but it is also ever-changing.

My book does not write much about the history, or politics, or economics of these places I refer to. My aim was a much more modest one — to simply try to describe the lived reality, at least for me, of what it was like to move, taste, smell, see, and hear in these places. What was their sensory impact? How did they make me feel? What was it like as one human being from another very different environment (the UK, where I was born and brought up) to be immersed in a place with a very different feel — different climate, different light and different smells and sensations?

The lived reality of China is all too often forgotten in the grand geopolitical story we are exposed to in the media. There the narrative has to be boiled down to good or bad, positive or negative. It often seems lacking in any human element at all. For me, however, I experienced China as a person, speaking to other people, and learning about the place through them. For thirty years, I have been able to enjoy wonderful friendships with Chinese colleagues. I have learned from Chinese students, and am still being taught by them! This human element is too easily forgotten. But it is utterly critical. China is for sure a place, but it is also a community of people, and it only makes sense on the level of people-to-people links.

An elementary school student learns Chinese calligraphy during the “China Cultural Week” on May 15 in Zagreb, Croatia. (Photo/Xinhua)

In the last two decades, hundreds of thousands of Chinese have come abroad to study. In the past, for someone to now know much about the country when living outside it was at least excusable because there was a relative lack of contact. Few Chinese before the 2000s came to the UK, for instance. Few British went to China. But now, this is simply no longer the case. So when one comes across someone like the interviewee referred to above who has strong opinions about China and no evidence of any real knowledge, then the easiest remedy would be to suggest to them they take time to talk to the many students who are now based in the UK. Hearing their very different stories would at least introduce a little more depth and complexity.

I suspect however that this would not be a comfortable experience for someone so invested in what is, in the end at least, a fiercely held illusion. It is a good thing that for most other people curiosity and a willingness to learn about somewhere so different to their home environment is still strong. And for them, I can only say that China, for all its challenges and complexities, is also an extraordinary teacher. That is, of course, if one is willing to learn!