Poverty and democracy are both weasel words, obscure in their meaning but strong in their moral connotations. In a world forced into unneeded ideological competition, such words are used to kill debate and inquiry rather than to promote mutual understanding.

Poverty is indisputably bad while democracy is inherently good. No-one wishes to increase poverty or to criticise democracy. The word ‘poverty’ creates moral pressures to eradicate it, while the same morality demands that democracy should be defended. But without agreed definitions both terms are vacuous, bastions of obscurity and causes of confusion. The blend of strong moral purpose with ill-defined goals and ambiguity fuels bigotry and is exploited by demagogues and aggressors alike. Both words become weapons used to create enemies, sow discord and protect the interests of the rich and privileged who buy influence and votes to circumvent democracy.

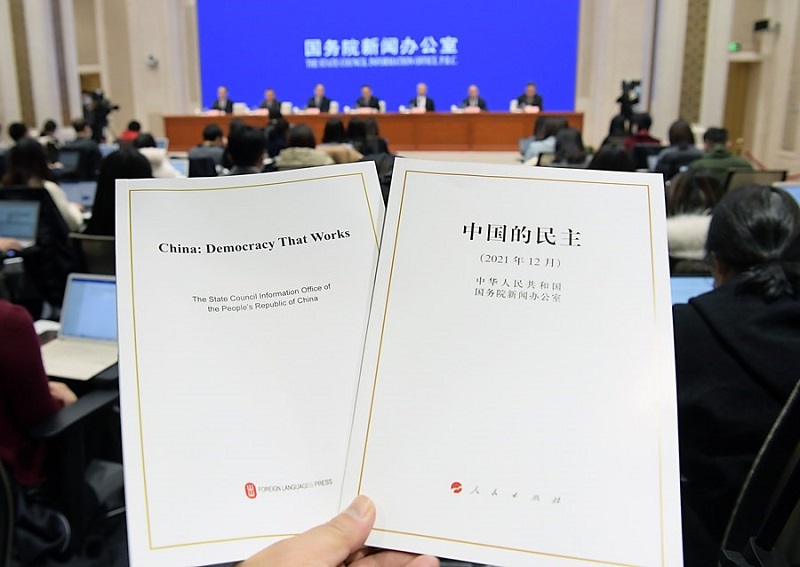

Photo shows the Chinese and English editions of the white paper titled "China: Democracy That Works" at a press conference held by the State Council Information Office in Beijing, capital of China, Dec. 4, 2021. (Xinhua/Li He)

To have reached this impasse is a major impediment to global progress. Democracy, to borrow the language of the white paper “China: Democracy That Works” recently published by China’s State Council Information Office, is ‘a common value of humanity,’ one that is universally cherished. Furthermore, the world needs to be united in tackling poverty under the rubric of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

To reclaim both these words from their role as weapons of ideological warfare, to transform them into tools for international cooperation, it is necessary to accept that neither is truly a binary concept. Poverty is inherently relative, materially different in varying settings, but everywhere a failure of governance, personally painful and socially destructive. Democracy in English, as the Merriam-Webster dictionary makes clear, has no perfect antonym, only ‘near-antonyms’ like despotism and dictatorship. It is an ‘all or nothing’ concept allowing for no variation. The concept itself, therefore, is dictatorial, denying freedom in the design and implementation of democracy. In reality, of course, there are many kinds of democracy not one.

There are, though, common strands. Perhaps the best way to determine whether a country’s political system is democratic is to note whether “the succession of its leaders is orderly and in line with the law, whether all the people can manage state and social affairs and economic and cultural undertakings in conformity with legal provisions, whether the public can express their requirements without hindrance, whether all sectors can efficiently participate in the country’s political affairs, whether national decision-making can be conducted in a rational and democratic way, whether people of high calibre in all fields can be part of the national leadership and administrative systems through fair competition, whether the governing party is in charge of state affairs in accordance with the Constitution and the law, and whether the exercise of power can be kept under effective restraint and supervision.”

This public road built along the cliffs helps connect Huawu Village in Qianxi County of Guizhou Province, an ethnic Miao community, with the outside world. Shi Kaixin

Given thought, few would deny the merits of this definition of democracy taken from the Chinese white paper. However, much thinner definitions of democracy often frame the global debate. A common metric is the one originally developed in 1972 by Raymond Gastil, a regional studies specialist teaching at the University of Washington in Seattle. This is now used each year to evaluate the political systems of almost 200 countries by Freedom House, a ‘non-partisan organisation’ based in Washington D.C.

The scale assigns a 40 percent weight to political rights and one of 60 percent to freedom. This ratio arguably reflects the American concept of liberty as defined in, for example, the 1776 Declaration of Independence. Liberty is understood to be freedom from state interference and this, in turn, reflects the experience and attitudes of European emigres arriving in America in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Many of them were fleeing from state-condoned religious repression. Therefore, the concept of a government being virtuous and benevolent, as derived from Confucian thought, is alien to the American polity.

A ‘thicker’ definition of democracy is that employed by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), the research and analysis division of the Economist Group. This employs 60 indicators to reflect five dimensions of democracy: electoral process and pluralism; civil liberties; the functioning of government; political participation; and political culture. Irrespective of definition, however, electorates in established democracies have become increasingly dissatisfied with their system of government.

A study published by the Pew Research Center in December 2021 reports that, in countries across the globe, democratic norms and civil liberties have deteriorated. Asked in spring 2021, a median of 56 percent respondents in 17 democracies with advanced economies said that their political system needed major changes or to be completely reformed. This was true of 89 percent of respondents in Italy, 86 per cent in Spain, 85 per cent in the United States and 84 per cent in South Korea. At least two fifths of people in each of these countries, South Korea excepted, specifically said that they were dissatisfied with the way that democracy was working.

The most powerful predictor of respondents demanding change were those who were unhappy with the current state of the national economy. Supporting this, a very careful study by two economists at Yale University, Yusuke Narita and Ayumi Sudo, has recently demonstrated that, since 2000, democracies have registered less economic growth than jurisdictions with other forms of government.

Despite their faltering economies, there are several arguments why democracies should be better at reducing poverty than other kinds of governance. People in poverty are enfranchised to vote and politicians should therefore respond to their needs. An investigative press should alert governments to the individual hardships and social cost of poverty. Also, in democracies, governments respond to the will of the median voter. Because incomes in capitalist economies are always very unequal, the income of the median voter will be less than the average. This means that the median voter will rationally demand a downwards redistribution of income that might also benefit the least well off.

However, there is no evidence among rich countries that democracy itself leads to reduced poverty. On the other hand, honest politics can. Based on OECD data base, relative poverty is lowest in social democratic countries that prioritise social solidarity and high in liberal welfare regimes like the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia that believe in small governments and market solutions. It should be acknowledged, though, that, according to the EIU’s democracy measure, the USA is not a full democracy. It is a ‘flawed’ one.

Poverty is measured differently in developing countries. The poverty line is fixed at income of less than US $1.90 a day. None of the developing countries for which poverty statistics are available is a full democracy accorded to the EIU standard. This raises the possibility that eradicating poverty allows democracy to develop rather than that democracy reduces poverty. Certainly, those developing countries with partial, albeit flawed, democracies were no more likely to reduce poverty between 2000 and 2015 than other types of government. What reduced poverty was economic growth. This perhaps helps to explain why China, during this period, lowered poverty by more than any other country.

So why does democracy not reduce poverty? The likely answer is that, once poverty in a country falls below 50 percent, low-income voters must build coalitions with others prepared to be altruistic. Unfortunately, electorates generally prioritise their own self-interest. And few politicians are brave enough to try to persuade electorates to vote for policies that benefit people poorer than themselves.

Likewise, few democratically elected leaders in rich democracies are sufficiently bold to devote 0.7 percent of gross national income to assist developing countries to tackle poverty. This is despite all countries agreeing to do so at the United Nations General Assembly on October 24, 1970. Four of the seven countries that have ever met this target are the same social democratic countries with the lowest poverty rates at home. Their commitment to social solidarity crosses national borders. More typically, the view of electorates in rich democracies is that charity begins and remains at home. There can be no better examples of this than first, the hoarding of COVID-19 vaccines while people in poorer countries die unvaccinated. And secondly, Britain slashing its aid budget because, in the words of the Prime Minister, it was needed at home ‘during the economic hurricane caused by COVID.’

Confucius recognised that poverty was evidence of poor governance and a source of social instability. It is not democracy per se, therefore, that eradicates poverty. It is good government and political leaders willing to convince electorates that what is morally right is socially beneficial.

___________

ROBERT WALKER is a professor with China Academy of Social Management/School of Sociology, Beijing Normal University, and professor emeritus and emeritus fellow of Green Templeton College, University of Oxford.