THE Spring Festival (China’s lunar New Year) is the country’s most important traditional festival. This year it falls on February 16. Although Spring Festival celebration customs vary from place to place, hanging red couplets (a type of paper banner with auspicious words) and setting off firecrackers are a “must” for all Chinese households.

As a traditional custom for more than 2,000 years, setting off firecrackers were initially believed to drive away a monster called nian according to a legend. It was said that the monster would befall the human society to bring evil on the Chinese New Year Eve. However, it was afraid of loud sounds. To scare the monster away, people burned bamboo joints, which created a loud, crackling sounds. Thus, celebrating the Spring Festival is also called guonian in Chinese.

Setting off firecrackers is a traditional custom to celebrate festive days in China.

The first firecrackers were made of bamboo. After gunpowder was invented, people stuffed nitre, sulphur, and charcoal into the hollow bamboo tube. After lighting it, it emitted a popping sound. Later, people replaced the bamboo tube with a paper roll filled with gunpowder. Following this, more and more firecracker varieties became available, featuring one bang or two bangs, or even a bunch of crackers tied together with hundreds or even thousands of explosive sounds produced after ignition. Among them, a type of firework, without a deafening sound, but featuring beautiful colored rays displayed just like blooming flowers, became the favorite of women and children.

It’s also customary for Chinese people to have a family reunion dinner on Chinese New Year Eve, an auspicious gesture to wish for security and health in the coming year. After dinner, family members would sit together to wait for the arrival of the new lunar year. When it comes to the turning moment of the old and new lunar years, the sound of loud fireworks can be heard everywhere. Setting off fireworks is the most important thing at this moment. It’s believed that all bad things would disperse with the burning of fireworks, and the new year would be a happy journey.

Evolving from the Spring Festival tradition, fireworks later began to be used in other celebration events, like weddings, groundbreaking ceremonies of projects, building completion ceremonies, and the inauguration of a company.

Liuyang’s Firework and Cracker Craftsmanship

“Fireworks are not just chemical products, but a result of culture and art. The firework craftsmen are a special type of painter, who take the sky as their canvas, sparkly explosives as their pigment, and making techniques as their brush; all these constitute the firework’s magic,” an artist once said.

Liuyang City in Central China’s Hunan Province is a major firework and cracker production base, also internationally known as the “city of Chinese fireworks.” Owing to its reputation, having once even won an award at the Chicago World’s Fair, fireworks and crackers here are also major local export commodities, sold to over 100 countries and regions.

In ancient times, the production of fireworks and crackers was mainly to meet the celebration needs of the feudal government. As a legend states, when Emperor Yongzheng of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) was enthroned, bangers and sparklers were required to be set off on the Lantern Festival. Then the order was issued that firework producers should create new varieties of fireworks and crackers as their royal tribute. Liuyang’s officials grew nervous, and soon posted an invite for firework-making talents. The pressure was then transferred to Li Tai, a master of this industry, who was ordered to create new fireworks in a short time. Li became very anxious. One day, when passing by a blacksmith’s shop, he saw sparks and flashes bursting under the blacksmith’s hammer, long and short, red and white, thick and thin, some as particles, some in filaments, which immediately inspired him. He collected some iron chips and shattered them with a hammer, then mixed them with gunpowder and rice soup. Black nitre was used as the propellant and installed at the bottom connected with the fuse, allowing the firework to eject a great variety of sparkling shapes. Li’s new fireworks were set off into the sky in the Forbidden City, and blasted a dazzling rain of shimmering flowers, which greatly charmed the emperor. Since then, Liuyang has enjoyed the reputation “city of fireworks.”

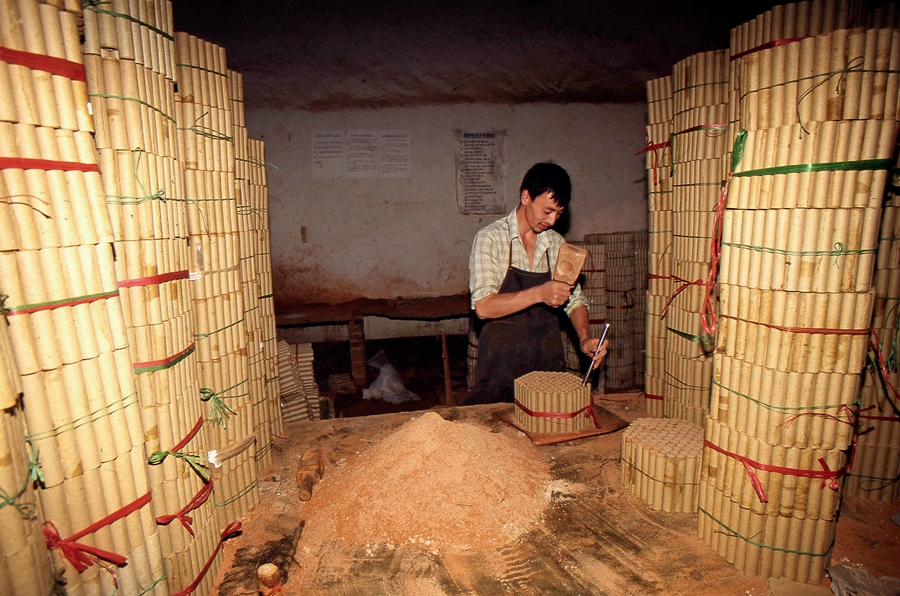

The firework production in Liuyang still features traditional craftsmanship with local handmade paper, potassium nitrate, sulphur, and carbon powder, red and white clay as production materials. Altogether 12 assembly procedures including 72 steps are required. Benefiting from modern technology, safe and harmless smoke-free fireworks, cold light fireworks, daytime fireworks, and fireworks for indoor entertainment and stage effects have all been created. Remote ignition has even become available, with only a computer able to control the whole ignition process. Liuyang’s fireworks can be classified into 13 categories covering more than 3,000 varieties. Among them, cold light fireworks are popular, environmentally-friendly products, non-toxic and odorless; owing to the low ignition temperature, people can touch them with their hands. In 2006, Liuyang’s high craftsmanship of fireworks entered the list of the first batch of national intangible cultural heritages.

Firework Making Craftsmanship in Pingxiang

Shangli County of Jiangxi Province’s Pingxiang City has been regarded as the birthplace of China’s fireworks and crackers. Historical documents indicate that Li Tian (621-691) from Shangli County improved the firework making artisanship. He drilled a hole in a bamboo tube, filling it with saltpeter powder, and then sealed the hole with pine tar. After ignition, the explosive force was much stronger than burning an ordinary bamboo tube. Soon after, Li’s neighbors began to follow the practice. To make it more portable and safe, Li later tried to replace bamboo tubes with paper tubes. After repeated experiments, the rudimentary form of modern firecrackers took shape. Due to this, Li is considered to be the creator of firecrackers. Every year on his birthday, the 18th day of the fourth lunar month, people in the local firecracker profession hold ceremonies to commemorate him.

The firework production in Liuyang highlights traditional craftsmanship.

In the 17th century, the firecracker industry boomed in Shangli County as almost all households made firecrackers. Shangli became a national firecracker production and distribution center, seeing an influx of traders from other places, who set up firecracker businesses and sold them to other provinces and cities like Guangdong, Fujian, Shanxi, Shanghai, and Hong Kong, and even exported them to Southeast Asian countries.

The traditional firecracker made in Shangli usually requires 15 procedures. Over the past several decades, Shangli’s firework and firecracker industry has seen fast development. With the use of machines, the production efficiency has been greatly improved, and production cost reduced. Remote operation and automatic control has been used in dangerous procedures, thus ensuring production safety. A firework and firecracker research institute was even founded in the county to train practitioners in the profession. In August 1987, in an international firework display competition held in Spain, China’s Jiangxi delegation secured second place with seven products awarded.

In 2008, Shangli’s traditional fireworks and firecrackers craftmanship was included into the list of the second batch of national intangible cultural heritages.

Frame-supported Firework Art in Pucheng

In Pucheng County of Shannxi Province’s Weinan City, there is an old form of fireworks that utilizes a support frame made of poles, thus acquiring its name ganhuo (literally meaning poled firework). Varieties of different fireworks are fixed to the poles, with each section displaying a different pattern and color combination. It’s also China’s sole surviving low-range form of firework art. The local tradition to pass down this technique only to a family male heir has added a touch of mystery to this style of frame-supported fireworks.

In a ritual event offering sacrifice to the sea in Jimo City of East China’s Shandong Province, fishermen set off clusters of red firecrackers.

Ganhuo is completely hand-made with a set of complicated making procedures required. The firework making craftsmanship distinguishes itself from others with a unique gunpowder formula and special requirements for materials, with extensive use of materials like straw, wood, iron chips, bamboo, paper, cloth, gauze, and silk fabric. A range of elaborate crafts are involved in making the special type of fireworks including bundling, toasting, mounting, knitting, painting, drawing, and packing.

Regarding the design process, ganhuo is divided into wenhuo and wuhuo, with the former focusing more on shape building. Based on the desired display of the fireworks, a special fuse is designed to ignite the fireworks in a specified pattern. To make a wuhuo, a frame is built with iron sticks or bamboo poles, and then fireworks are attached at certain points depending on the pattern, with a central fuse that connects everything. Usually it takes three to five days to complete a ganhuo. Complex designs require nearly a month. A ganhuo can be as tall as 20 meters with 12-24 different levels of fireworks.

In a transitioning society seeing upgrading industrialization, ganhuo stands out as a purely hand-made product. Its irreplaceable traditional artistry can vividly present fairy tales, magnificent architectural feats, and a variety of personages, leading people into a dreamlike wonderland.

When lit, the firework often amazes viewers with overwhelmingly impressive spectacles or enchanting flash-made pictures, touching on all facets of human society.

As people’s environmental-protection awareness improves, Pucheng has developed a new gunpowder formula without sulphur, which has made ganhuo greener and safer.

In 2008, the Pucheng ganhuo craftsmanship entered the list of China’s national intangible cultural heritage.

(Compiled by China Today)