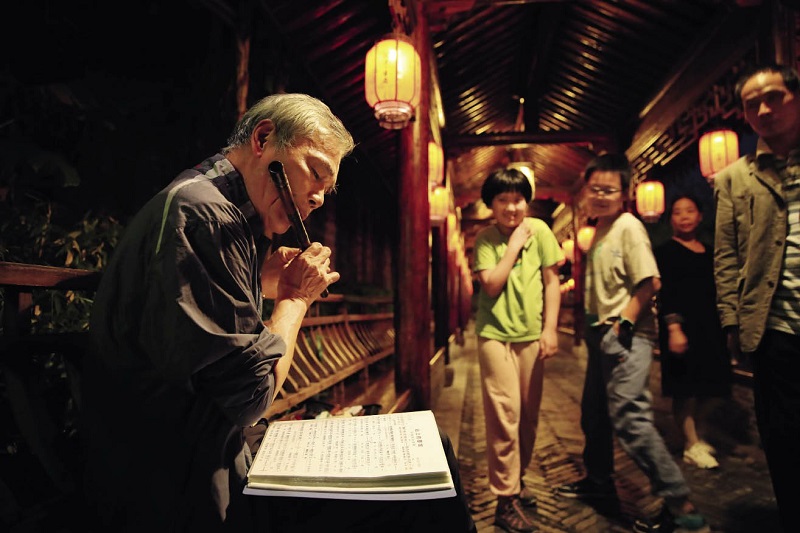

A resident plays dizi in Tianyi Pavilion beside the Moon River in Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, October 1, 2020.

Emperor Xuanzong (685-762) of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) has been renowned for his versatility, particularly in music. There are many anecdotes about the talented emperor. Once, while sitting at court, Emperor Xuanzong kept moving his fingers up and down his stomach. After the court was dismissed, Gao Lishi, the royal steward, came in and asked the emperor, “Your Majesty, I noticed you pressing your fingers up and down your abdomen. Are you feeling unwell?” Emperor Xuanzong replied, “No, I am fine. Last night I dreamed I was visiting the Moon Palace, and the fairies played celestial music for me. The melody was so captivating that I was totally engrossed in it. Later, the fairies played music again to see me off. The heavenly tune was wistful, intoxicating, and moving. When I woke up, I felt the melody was still ringing in my ears, so I wrote it down right away. I was afraid of forgetting the beautiful music, so this morning I kept playing the rhythm with my fingers to keep it fresh in my mind.” The instrument that Emperor Xuanzong finally used to record this “fairy music” was dizi, a Chinese flute. It is a traditional Chinese wind instrument with a history of over 8,000 years.

A resident plays dizi in Tianyi Pavilion beside the Moon River in Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, October 1, 2020.

The Oldest Chinese Musical Instrument

Dizi has a long history that dates all the way back to the Neolithic age. At that time, our ancestors drilled holes in tibia of birds and blew them to trap prey and convey signals. Thus, the oldest Chinese wind musical instrument – the bone flute, was born.

Before the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), the word dizi mostly referred to the vertical flute. During the reign of Emperor Wudi (156-87 BC) of the Han Dynasty, transverse flutes emerged on the scene. Since then, transverse flutes began to occupy an important place in the orchestra of the court and the military. By the Tang Dynasty, transverse flutes and vertical flutes were called di and xiao respectively. Many emperors such as Taizong (Li Shimin) and Xuanzong (Li Longji) of Tang personally enjoyed playing dizi and often organized orchestra performances in the court. Understandably, under the favor of the royal family, dizi quickly gained popularity during the Tang Dynasty. With the rise of poetry and the boom of operas in the Song (960-1279) and Yuan (1279-1368) dynasties, dizi soon became an accompanying instrument for many types of shows. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the great dizi player Feng Zicun introduced this traditional Chinese musical instrument to the stage of solo performance.

Wang Xi is playing dizi at the opening ceremony of the third Bamboo Flute Culture and Art Festival in Datong, Shanxi Province, on August 13, 2020.

Cultural Connotations and Mirthful Charm

Bamboo, which is the material commonly used for making dizi since about 4,000 years ago, symbolizes the virtues of modesty and tenacity in China. In a culture where bamboo has been endowed with such bountiful cultural connotations, it is not surprising that there is a long history of grading the numerous species of bamboo for their special qualities. Most dizi are made from bitter bamboo, purple bamboo, white bamboo, and Xiangfei bamboo. To begin making a dizi, a suitable piece of bamboo is selected and then placed in the shade to dry. After that, a series of procedures is followed that include cutting, lacquering, drilling, proofing, winding, and engraving. The straight shape of the dizi also reflects the Chinese cultural quality of integrity and perseverance. Being inculcated these cultural implications, dizi players have been retaining and passing down the tenacity and unyielding spirit of Chinese culture from generation to generation for thousands of years.

The timbre of dizi is generally mellow, fresh, and bright. Typically, dizi can be divided into two main genres. The southern branch of dizi produces elegant and clear sounds, mainly represented by qudi (often used in the accompaniment of Kunqu Opera). The timbre of the qudi is much mellower and clearer than other types of dizi. It can produce melodious, euphemistic, and exquisite tunes, showing the vivid style from the south of the Yangtze River. Qudi players often use tremolos and repetition in their performances. The northern genre of dizi, featuring strong and rough sound, usually refers to bangdi, which is generally used in northern Chinese folk operas. A bangdi is slim and short, and has a higher pitch and brighter sound. It is often used in presenting more lively and light scenes. Bangdi players prefer to use staccatos, glissandos, and other musical techniques.

With the social development and improvement of people’s aesthetic pursuits, in addition to qudi and bangdi, there are now more varieties of dizi in different sizes and with different timbres, such as the dingdiaodi (a fixed tone flute), diyindi (bass flute), koudi (mouth flute), paidi (row flute), judi (giant flute), and longdi (dragon flute). Despite the many varieties, the sounds they produce are generally clear, loud, and merry. The emotions and moods produced by the dizi are mostly about celebration, praise or joy. Even when playing a sad tune, the sound produced by dizi players is mournful but not resentful.

A worker inspects bamboo used to make dizi and xiao in his workshop at the manufacturing plant of Yuping Dong Autonomous County, Tongren City, Guizhou Province, March 23, 2019.

Interest Is the Best Motivation

Wang Xi is a professor at Minzu University of China and a young dizi performer. During his childhood, often watching his father playing dizi and teaching students to play it at home, his curiosity in the instrument was aroused. One day Wang saw a dizi on his father’s desk, he picked it up and tried to blow it, to his surprise, he could not only make a sound but even play simple tunes. Wang soon became obsessed with the musical instrument and began to learn it at the feet of his father. Sometime later, a friend of Wang’s father visited their home and Wang’s father asked Wang to play a music piece for the family guest. After his performance, the guest asked Wang if he would like to continue studying dizi with him. Wang readily agreed due to his genuine interest. Later, he learned that his father’s friend was Zhang Weiliang, the “King of Chinese Flute.”

Because of his own experience, Wang has always believed that interest is the best motivation for people to learn an instrument. Today, Wang not only teaches dizi playing techniques at the university, but also takes the instrument into primary and middle school classrooms. Wang explains to the children the basic concepts and culture of this traditional Chinese instrument, so as to foster an interest in them at an early age to spread and pass the ancient instrument on to future generations. The students enjoy listening to Wang’s performance and lectures about the dizi. During activity time, they have opportunities to touch different types of dizi themselves. Professor Wang has seen more and more opportunities to promote dizi and its cultural knowledge in recent years thanks to the increasing support from the government. At the same time, he hopes he can do more to expose children to traditional musical instruments and traditional culture.

New Elements Matter to the Ancient Instrument

As a master player of dizi, Wang has witnessed the musical instrument’s booming development in recent years. In addition to daily teaching in schools, Wang also teaches children how to play dizi in his spare time. “I’ve taught tens of thousands of students,” Wang said, “and there are a great number of dizi professionals like me who are devoted to promoting this musical instrument and Chinese culture.” Overall, the modern development trend of dizi is steadily improving. At the same time, as the country attaches more importance to traditional culture, more people will pay attention to this ancient Chinese instrument.

Nowadays, more and more players are using dizi to perform popular music at home and abroad, thus infusing new vitality into the ancient instrument. In addition to playing dizi, Wang also composes songs for dizi in pop or jazz music styles. Wang believes that each generation has their own unique aesthetics and understanding of culture, which thus endow music works with specific cultural connotations. As an ancient Chinese musical instrument, dizi has to be continuously integrated with modern culture and styles of music in order to reach succeeding generations, Wang indicated.

QR code for interview video