The ideology of being ready to make innovation and keeping abreast of the times is a defining feature of the Chinese civilization.

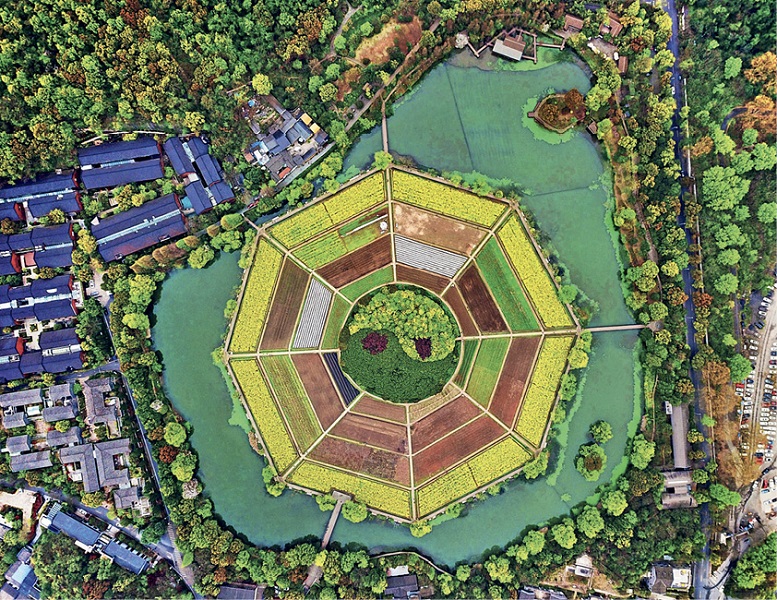

The Eight Diagrams Field Park in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province in east China, is built on what used to be royal farmland during the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279).

In several of his recent speeches President Xi Jinping stressed that the Chinese civilization has the tradition of discarding the outdated in favor of the new and moving ahead with the times. In exploring a new philosophy that is suitable for governing China in the new era, China draws on its fine traditional culture to find ways of abolishing outdated ideas and making theoretical, practical, and institutional innovations, thus staying abreast of the time to create a better future.

In ancient China during the Pre-Qin period (before 221 B.C.), the phrase “革故鼎新 (Ge Gu Ding Xin),” which means discarding the outdated in favor of the new, was used to express a quality of the Chinese civilization that has defined its enduring vitality as a nation. This term can be traced back to two hexagrams in the Book of Changes – Ge and Ding. The former stands for discarding the old, and the latter establishing the new. Together they mean replacing obsolete ideas and institutions that hinder development with new ones that cater to the progress of the present time. It is the combination of discarding the old and establishing the new that creates a driving force for propelling global development.

A Path to Personal Growth

In a rapidly changing world, everyone needs to keep acquiring new knowledge and putting it into practice. Only through constant self-improvement can we adapt to the changing times, advances in technology, and social progress. A line in the Book of Rites, a collection of texts describing the social norms, administration, and ceremonial rites of the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 B.C.), says, “If you can improve yourself in a day, do so each day, forever building on improvement.” This dictum was a central philosophy of Tang, founder of the Shang Dynasty (C. 1600–1100 B.C.), so much so that he had it inscribed on his bathtub. Every time the monarch took a bath, he was reminded to take time for self-reflection, self-correction, and self-improvement, in order to continue improving his governance of the state.

Reluctance or refusal to accept change will lead an individual or a state nowhere, as demonstrated in the story of a man from Chu in the Master Lü’s Spring and Autumn Annals. According to the story, there once was a man who accidently dropped his sword into a river while crossing to the other side. He quickly made a mark on the side of the boat where the sword had slipped into the water and told himself, “This is where my sword fell.” When the boat reached its destination, he searched for his sword in the water below the mark, but of course, to no avail. To avoid making a fool out of oneself by “marking a moving boat to look for the sword later,” one should embrace the old wisdom of “discarding the outdated in favor of the new,” and strive for personal growth in knowledge and morality.

A Driving Force Behind Social Development

During the last years of the Shang Dynasty, intensifying social conflicts and mounting grievances of the people brought the old societal order based on primitive theocracy to the verge of collapse. In response, Duke Ji Chang (C. 1152–1056 B.C.) and his son Ji Fa introduced progressive economic policies and lenient laws in their kingdom that helped expand the economy and gain the people’s support. Ji Fa later overthrew Shang and established the Western Zhou Dynasty (C. 1100–771 B.C.).

When helping with state affairs, Ji Fa’s brother Dan, a great statesman, thinker, and educator, occupied himself with answering the question: Why did the previous two dynasties Xia and Shang decline and fall? He believed that to ensure the enduring rule of the country, Zhou must establish a new social system. He hence conducted extensive research on the systems of past eras, modified their policies to fit contemporary conditions, and devised laws in various fields, such as music and rituals, social behavior, and public relations. As a result, his reforms profoundly impacted politics and the society at large, propelling the evolution and progress of the Chinese nation and civilization.

A Principle for Inheriting and Developing China's Traditional Culture

Prior to Confucius, education was something exclusively available to the nobility, as common people were not allowed to attend state-run schools. Confucius nevertheless believed that education should be made universal, and knowledge should benefit society instead of being used as a tool to maintain the prerogative of aristocrats.

With a firm commitment to reform and innovation, Confucius founded the first private school in Chinese history, welcoming anyone who was willing to learn regardless of their family background. An early token of the idea of educational equity, the school attracted students from different regions and all social status. Many of them later became the leading intellectual and moral figures of their times, making important contributions to social progress. With the courage to abolish old ideas and practices, Confucius introduced new didactic methods and approaches, becoming a pioneer in education.

An Approach to Achieving Economic Takeoff

Since the 1980s, China has proceeded with the reform and opening-up policy and continued to make steady progress. This has included removing outdated systems, mechanisms, and regulations which had hindered economic development and social progress. As a result, it has fostered a favorable environment for economic growth, enhanced protection of people's democratic rights, unleashed their creative potential, achieved a miraculous 40-year-long economic boom, and eradicated absolute poverty.

Leaving the beaten path to blaze a new trail and smashing old conventions to install new ones has always been part of the cultural genetics of Chinese people. Over the past 2,000 years, this is exactly what China did when it got bogged down in stagnation or encountered setbacks. As China keeps pressing ahead and breaking new ground, it will become more democratic and prosperous, Chinese people’s lives will enjoy greater freedom, and their civilization will grow more vibrant and diversified.

The Tang Dynasty poet Liu Yuxi (772–842) once wrote, “New leaves sprout, urging the dead ones to fall; earlier tides recede, making way for those that follow.” In its modernization drive, China has taken innovative steps to follow the tradition of updating the outdated, advancing reform and injecting fresh energy into economic, social, and cultural development.

QI YU is an assistant researcher with the Confucius Research Institute.