“A civilization exceling in poetry, China possesses a language of beauty that theater can carry to the world. Just as Chinese audiences appreciate Shakespeare, so too can global audiences discover the magic power of Chinese verse and the profound resonance of its culture on stage,” said Tian Qinxin, president of the National Theater of China, in an exclusive interview with China Today.

Tian is a prominent figure in the theater world and also sits on the Standing Committee of the 14th National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), China’s top political advisory body. As a theater director, she has staged many landmark productions, ranging from Four Generations Under One Roof, Beijing Fayuan Temple, Green Snake, and The Orphan of Zhao to the more recent The Summoning of Dunhuang and Spring Dawn on Su Causeway. In recent years, she has also pioneered a contemporary theatrical language to share China’s stories with global audiences and to spark dialogue among civilizations.

Tian Qinxin, president of the National Theater of China.

Decoding Chinese Aesthetic

When asked which of her works best exemplifies Chinese theater “going global,” Tian answered Green Snake. Ten years ago, the play was invited to The World Stages – 2014 International Theater Festival at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., and later appeared at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. Meanwhile, in 2024, to celebrate the 60th anniversary of diplomatic relations between China and France and the China-France Year of Culture and Tourism, a high-definition video of Green Snake, with French-language subtitles, was screened at the Versailles Convention Center near Paris. Adapted from a classic Chinese legend, the play was given a fresh perspective and new life by its director and playwright Tian, receiving standing ovations from audiences.

Tian pointed out that Green Snake itself is a product of international collaboration. The set designer is German, and the lighting designer and composer are Scottish. Technical support was provided by the National Theatre of Scotland. A Sino-European ensemble of artists crafted a singular stage language for this beloved Chinese folk tale, conjuring up the mist-soaked grace of south China.

“What is most national is also most universal,” Tian emphasized. After watching the play at the Hong Kong Arts Festival, the artistic director of John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts immediately extended an invitation to the troupe to perform in the United States.

“I was surprised that this Chinese folk story struck a chord among Western audiences,” Tian recalled. “Instead of feeling puzzled, they felt an immediate pull toward the Chinese aesthetic and responded with strong artistic empathy.” Enchanted by the serpentine grace of White Snake and Green Snake, many American theater goers asked, wide-eyed, “Are all Chinese girls so supple?” When told the tale is set in southeast China’s Hangzhou, they vowed, “Then we have to go there and see for ourselves.”

In Tian’s view, Green Snake presents distinctive Chinese aesthetic – Chinese romanticism and boldness, entwined with explorations of desire, faith, independence and perseverance. “This Chinese aesthetic is a unique presence on the international stage,” she said.

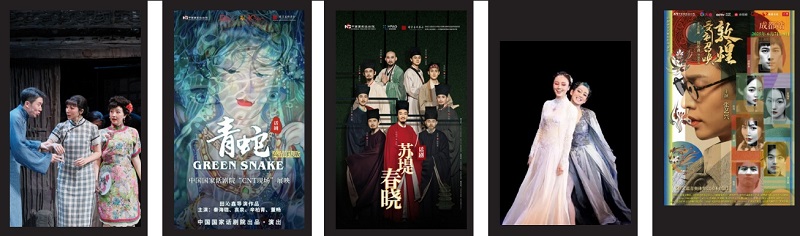

From left to right: Stage photo of Four Generations Under One Roof. The poster of Green Snake. The poster of Spring Dawn on Su Causeway. Stage photo of Green Snake. The poster of The Summoning of Dunhuang.

Four Generations Under One Roof is another production that has made a big impact across Asia, with sold-out runs in Hong Kong, Macao and Singapore. The play, spanning 14 turbulent years, depicts the everyday lives of ordinary residents of a Beijing hutong during the Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression. “This realist drama demands highly naturalistic acting. Its time span and the theme of family and nation push the actors to their limits,” Tian observed. “All the characters are ordinary people, making it a ‘civilian epic’ and striking a common emotional chord throughout Asia.”

A group photo of the cast of Four Generations Under One Roof.

“Recently, we’ve been preparing to take Spring Dawn on Su Causeway to overseas audiences,” Tian said. Set in the Northern Song (960-1127), the play chronicles the life of the great writer Su Dongpo (1037-1101) and seeks to make Song dynasty culture flow into a new era.

During the creation process, the National Theater of China’s creative team delved deeply into the essence and contemporary relevance of Song Dynasty culture, striving to present a sweeping scroll painting of the Northern Song on a small stage.

Tian noted that Su Dongpo, as a master of Chinese literature, already has a large following among Sinologists overseas, particularly in Japan, Republic of Korea and Vietnam. “The world knows Pushkin, Goethe and Shakespeare,” she said. “Su Dongpo’s unique temperament, integrity, and talent deserves the same global spotlight.”

Stage photo of Spring Dawn on Su Causeway.

Tech-Driven Cultural Revival

How can traditional culture merge with modern life, and how can classical literature integrate with modern theatrical art to create masterpieces? Tian believes this is a question every artist must answer. Such integration, she said, is not a matter of simple juxtaposition, but of profound cultural awakening. Five millennia of Chinese civilization are not dusty relics but an inexhaustible source of inspiration. “Only with cultural confidence and creative consciousness, can we truly revitalize tradition and allow it to shine in the present,” she said.

Tian has explored digital theater and new performing arts formats. “The marriage of technology and art constantly opens up the imagination. It is fascinating and worth exploring,” she told China Today. The music drama The Summoning of Dunhuang is one such experiment.

The play tells two stories of guardianship across one century. In 2035, a young man named Zhang Ran, living in the era of Digital Dunhuang, is inspired by the spirit of Chang Shuhong (1904-1994), founding director of the Dunhuang Academy, to devote his life to preserving Dunhuang’s art. A century earlier, in 1935, Chang, who was studying in France, was summoned by the artistic treasures of the Mogao Caves and decided to return to China to protect them. Two men in different eras both spend their lives safeguarding and passing on the cultural heritage of China.

Dunhuang, once a fertile oasis and international trading hub on the ancient Silk Road, was also a model of cross-cultural exchange. To recreate its former splendor that featured tender green in February and violet blooms in March, the creative team used AI, 3D special effects, real-time filming and two-dimensional animation for the first time. Inside Beijing’s National Speed Skating Oval, they built a multi-screen interactive set to enable rapid shifts between 1935 and 2035 and combined cinematic shooting with dimensional animation to deliver a film-like narrative.

The use of such artificial intelligence generated content or AIGC technology has revived Dunhuang’s former glory on stage, also restoring the Tang Dynasty (618-907) murals and painted sculptures to their original vividness. “Such bold experimentation allowed spectators to witness the infinite possibilities born of the collision between technology and art, while forging a cultural product that transcends borders and showcases the vitality of Chinese civilization and the sophistication of Chinese modernization on the global stage,” Tian said.

Stage photo of The Summoning of Dunhuang.

To continue promoting the creative transformation and innovative development of traditional Chinese culture, the National Theatre of China has, since 2022, held three seasons of the “Young Directors’ Incubation Programme,” combining artistic creation with the cultivation of young talent. Taking the modern reinterpretation of classical literature as its theme, the programme drew material from one of the four great classical novels of Chinese literature The Water Margin and a masterpiece of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) playwright Tang Xianzu’s (1550-1616) The Peony Pavilion, encouraging young directors to strengthen their basic training, explore fresh theatrical expression and discover new ways to blend tradition with modernity.

“We have supported 31 young directors and produced 32 small-theater works. Two of them – The Mystery of Jizhou and Three Lives Road – have been further developed into full-scale productions,” Tian said. Adapted from The Water Margin, The Mystery of Jizhou has enjoyed solid box-office returns and positive audience feedback since its 2023 premiere. A full-scale version of Three Lives Road, adapted from The Peony Pavilion, will be unveiled this year, allowing audiences to experience the timeless charm of a classic through a fresh, lively and accessible staging by young directors.

Looking ahead, Tian said, “We will also launch a ‘Young Playwrights’ Incubation Programme’ to nurture young playwrights, raise the quality of scripts, build a rich reserve of outstanding works and cultivate a high-caliber artistic talent pool.”

Director Tian Qinxin (second from right) takes a photo with the cast of Four Generations Under One Roof.

A Pioneer of Inter-Civilizational Exchanges

Art, as a cultural vehicle that transcends language and national borders, is uniquely capable of building bridges between hearts and presenting an authentic, multi-dimensional, and panoramic image of China, said Tian. She pointed out that Chinese President Xi Jinping had stressed the need to “integrate the basic tenets of Marxism with China’s fine traditional culture.” This, she said, furnishes the fundamental guide for developing a Chinese theatrical discourse that can converse with the world and is unmistakably ours.

She proposed the “Chinese perspectives on performance” amid efforts for Chinese theater to go global. To shed clarity on what it means, Tian breaks it down to three dimensions.

First, its roots run deep in the Chinese cultural vein. Chinese theater can be traced back to the court jesters of the pre-Qin period (2,100-221 B.C.), the variety shows of the Han (206 B.C.-A.D. 220), the poetic dramas set to music of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), and the Kunqu and Peking Opera of the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. Its intellectual palette was shaped by the confluence of Confucian, Buddhist and Daoist thoughts, highlighting “moral illumination and righteous principle” together with “loyal and patriotic sentiment toward family and nation.”

Second, its core lies in the fusion of “poetic sensibility” and gongfu, which means basic skills. “Poetic romanticism” grants Chinese theater its impressionistic and lyrical hue, while “gongfu-based expressionism” stresses the actor’s rigorous, codified, virtuosic craft.

Third, its soul resides in a distinctive performer–spectator compact. Chinese theater aspires to a dialectical state of “seemingly real yet not real, seemingly unreal yet real.” The actor, through consummate gongfu, presents a game of “impersonation,” while the audience, empathizing in a rhythm of “stepping in and out,” reaches an Eastern aesthetic accord with the stage – acknowledging the virtuosity without ever quite taking it real.

The audience is enjoying Four Generations Under One Roof at the Grand Theatre of Hong Kong Cultural Centre on July 4, 2025. Photos courtesy of the National Theater of China

.jpg) “On the path to forging a ‘Chinese perspective on performance,’ theater practitioners must strive to be pathfinders in cultural exchange and mutual learning,” Tian noted.

“On the path to forging a ‘Chinese perspective on performance,’ theater practitioners must strive to be pathfinders in cultural exchange and mutual learning,” Tian noted.“Our productions in the new era must delve deeply into the universally resonant core of Chinese culture so that Chinese stories embody both Chinese characteristics and Chinese aesthetics, while also re-activating cultural genes from a contemporary perspective to locate the ‘common ground’ where Chinese civilization can converse with the rest of the world,” Tian told China Today. When foreign audiences see in Chinese theater how Chinese people confront adversity, whether it be the personal trials of desire, faith, independence, and perseverance or the collective spirit of resisting invasion at the national level, and witness the Chinese understanding of “the unity of nature and humanity,” they will naturally feel the humanistic touch and profoundness of Chinese civilization. That, according to Tian, is one of the most powerful ways to sustain a dialogue among civilizations.