Groundbreaking translations of ancient Chinese medical classics into German and English shed new light on traditional Chinese medicine.

At first glance, 80-year-old professor Paul Ulrich Unschuld reveals a typical scholarly temperament. He is tall and serious, wears a plain black suit, and uses precise wording when he speaks. It seems to fit in with his academic background – as a medical historian, translator, and sinologist who hails from Germany and someone who has been tirelessly devoted to traditional Chinese medicine research for decades.

To date, he has translated classical Chinese medical works such as The Compendium of Materia Medica, Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon, and Classic on Medical Problems into English and German, which generously facilitates the communication between different civilizations in the field of medicinal science.

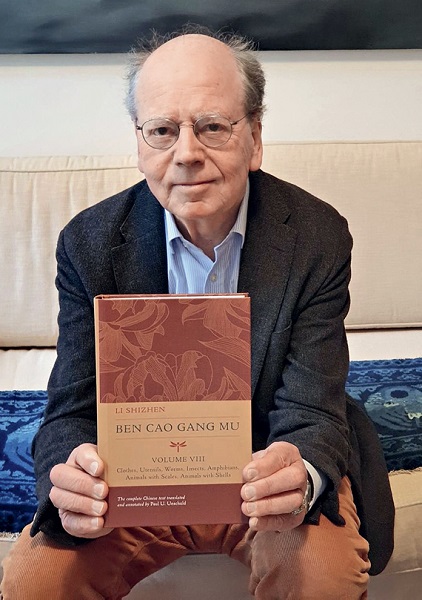

Professor Paul Ulrich Unschuld is holding Ben Cao Gang Mu, or The Compendium of Materia Medica, a Chinese medical classic he translated.

A Curious Mind

Unschuld was born into a pharmaceutical family. His father ran a small pharmacy and collected many ancient pharmacopoeias. His upbringing influenced his decision to major in drug research in college. In the 1960s, he and his wife Ulrike went to China’s Taiwan to study Chinese. During this period, they developed a strong curiosity for the history of Chinese medicine, which motivated Unschuld to embark on a path of traditional Chinese medicine research.

In the late 1970s China adopted the policy of reform and opening-up. At that time, there were few Westerners interested in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) therapies like acupuncture. As a scholar in this field, Unschuld was constantly invited to various lectures. He gradually found that Westerners had rarely interpreted TCM from a historical perspective. This made him realize the need to select the most representative texts from the vast history of TCM and translate them, so that the Western world could understand its roots and the ancient country it grew from.

This decision led him to embark on a lifelong translation career, which he never gave up even when he was battling with cancer in his later years. Over the past five decades, he has translated dozens of Chinese medical classics. The translation itself is arduous, with incomplete texts, historical names hard to verify, and diverse terminology. But to him, nothing is unconquerable and he approached each task with a rigorous academic attitude. When his translation of The Compendium of Materia Medica was published, Unschuld impressed readers with his translator’s “craftsmanship.”

The book is a medicinal classic and an encyclopedia of ancient China. It covers a wide range of natural sciences, including medicine, botany, zoology, mineralogy, chemistry, astronomy, geography, physics, and meteorology The difficulty of translation is immense.

In order to translate this work well, Unschuld and several Chinese experts first compiled three volumes of related dictionaries, in which they rigorously verified the terms they would need. The dictionaries served as the basis for subsequent translations. He first collaborated with Professor Zhang Zhibin, chief researcher of TCM history literature at the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (CACMS), to compile the first dictionary which identifies and defines the 4,500 diseases mentioned in The Compendium of Materia Medica. He then collaborated with Paul Buell, professor of history at the University of North Georgia in the United States, to complete the second volume based on information provided by Professor Hua Linfu of Renmin University of China, which confirms the ancient place names appearing in the book.

In the third volume, he worked with Professor Zheng Jinsheng from CACMS, who studies the history of Chinese pharmacy, Professor Paul Buell, and Ms. Nalini Krik, who teaches TCM therapy and sinology at a German institute for TCM training, to confirm the names of people who appeared in the book. In support of his work, Chinese entrepreneur Rong Yumin provided generous financial support.

It is precisely this diligence that has made Unschuld a prominent figure in the field of TCM classics translation. Apart from this, he is also committed to sharing his thoughts and ideas with others by attending lectures and explaining the methods of translation to young scholars. With the successive publication of his multiple translations, Unschuld has received such awards as the Best Translation Award at the Special Book Award of China and the Shulan Medical Outstanding Contribution Award from the Academician Shusen Lanjuan Talent Foundation, gradually becoming an icon in the field of TCM research.

Foreign students taking part in a hands-on learning activity about the efficacy of Chinese herbal medicine at a base for educating international students about TCM culture founded by Shandong University of Science and Technology in Qingdao, east China’s Shandong Province.

Philosophy and the Human Body

Today, as modern medicine is highly developed, many ask why someone like Unschuld still spends so much effort studying ancient Chinese medicine and what is its significance.

Unschuld gives a philosophical answer: “On the one hand, the records passed down from generation to generation by ancient Chinese doctors can provide inspiration for the development of medicine today and in the future. On the other hand, ancient Chinese medical classics allow us to understand the origin of Chinese medicine.”

He believes that the origin of medicine is accompanied by the sprouting of human rationalism. “Reading these ancient medical works, we can know when China began to establish medical science and attribute physical discomfort to diseases rather than supernatural beings. Like the medicine of ancient Greek, traditional Chinese medicine approached life on the basis of natural laws. Its theory of yin and yang and of the Five Elements reflect a pursuit of natural laws, which is highly revolutionary,” he said.

Translating and interpreting ancient Chinese medical literary works can also help promote cultural exchange. In Unschuld’s eyes, medicine is the application of philosophical ideas in addressing the sick human body, and the way people prevent and treat diseases is precisely the way they approach life. The medicine of different civilizations reflects their different philosophical ideas, and the comparison between Eastern medicine and European medicine is also a dialogue between the two civilizations.

“My favorite book is Miraculous Pivot of Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon,” said Unschuld. “This book is full of philosophical charm and contains many references to ancient Chinese thought, which give me insight into the social life of ancient China.”

A Beacon of Light for the Future

In October 2015, Chinese pharmacist Tu Youyou won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her discovery of new antimalarial drugs of artemisinin and dihydroartemisinin. Her inspiration for discovering artemisinin came from the fourth century Taoist Ge Hong’s pharmaceutical book A Handbook for Emergency Prescriptions - For Treating Cold and Heat Malaria. Inspired by ancient prescriptions, Tu used modern pharmacological and chemical methods to extract artemisinin, which saved many lives and once again brought TCM into the global limelight.

However, the task of making the world aware of the importance of TCM is still a long and arduous one. Unschuld admitted that although many people in Europe are supporters of acupuncture therapy, the group is still relatively small. He believes that ancient Chinese medicine and therapies urgently need modern medicine to prove their scientific nature for treatment.

Ancient medical literature remains of great value. Unschuld pointed out that since ancient times, Chinese doctors have been using various substances in nature to make medicine and have recorded thousands of prescriptions. Today, like Tu and her team, people can also search for clues to develop new drugs from these ancient prescriptions. This is exactly his original intention of translating ancient Chinese pharmaceutical classics.

In recent years, TCM has gradually gained international recognition in practical use. The unique Ginkgo biloba from China has been introduced to many countries around the world, and German scientists have extracted ingredients from it to treat diseases such as Alzheimers.

“This is also why people have been studying ancient Chinese therapies and prescriptions in a scientific way, and introducing them into modern medicine,” said Unschuld. “Of course, not only ancient Chinese medicine, [but] ancient Indian and Arab medicine as well as folk legends, are also valuable.”

For years, Unschuld has always regarded the dissemination of Chinese culture as part of his mission in life. His translations are groundbreaking, relying on strict philological and historical methods, and are faithful to the original text. He selects precise words to describe what TCM is, along with the worldview of ancient China.

By promoting the TCM culture to the world, said Unschuld, it allows the world to experience the illuminating moments of ancient Chinese sages. It also becomes a beacon of light to assist with the future development of medicine as a whole.