Many of the earliest Western adventurers to China elaborated in their writings about the symmetric structure of Beijing anchored on a central axis.

Known as a confluence of Eastern civilizations, ancient Beijing fascinated Europeans for its grand size and majestic buildings. At the core of the city is a 7.8-kilometer Central Axis that extends between the Drum Tower and Bell Tower in the north and the Yongding Gate in the south, along which stand many architectural icons that have been preserved to date.

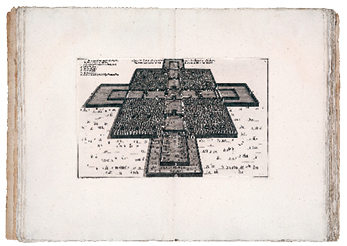

A map of the imperial city in Beijing drawn by Dutch traveler and explorer Johannes Nieuhof in the 17th century.

Marco Polo

The Venetian merchant and adventurer Marco Polo (1254-1324) traveled around Europe, Asia, and Africa for 25 years during the late 13th century, of which at least nine of those years were spent in Dadu, the name of Beijing during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). He later wrote about this cherished experience in the Travels of Marco Polo.

In his book we find the following description, “The streets [of Dadu] are so straight and wide that you can see right along them from end to end and from one gate to the other. And up and down the city there are beautiful palaces, and many great and fine hostelries, and fine houses in great numbers. All the plots of ground on which the houses of the city are built are four-square, and laid out with straight lines; all the plots being occupied by great and spacious palaces, with courts and gardens of proportionate size … Each square plot is encompassed by handsome streets for traffic; and thus the whole city is arranged in squares just like a chess-board, and disposed in a manner so perfect and masterly that it is impossible to give a description that should do it justice.”

This description coincides well with that about Dadu in ancient Chinese files. According to a book from the late Yuan Dynasty, the capital city of the empire was divided by broad roads from north to south and parallel alleys that ran from east to west at equal intervals. The north-south roads were called warps and the east-west ones were wefts. The former was 24-step-wide and the latter 12-step-wide.

The sprawling imperial city was the central architectural piece on the Central Axis, and Marco Polo gave a detailed account about it in his book, “The great wall has five gates on its southern face, the middle one being the great gate which is never opened on any occasion except when the Great Khan himself would go out and come in. Close on either side of this great gate is a smaller one by which all other people pass; and then towards each angle is another great gate, also open to people in general; so that on that side there are five gates in all.”

The most important building in the imperial city was the Daming Hall, where the Yuan emperor was enthroned, held the annual New Year’s ceremony, and celebrated his birthday. Marco Polo observed, “The Hall of the Palace is so large that it could easily dine 6,000 people; and it is quite a marvel to see how many rooms there are besides. The building is altogether so vast, so rich, and so beautiful, that no man on earth could design anything superior to it. The outside of the roof also is all colored with vermilion and yellow and green and blue and other hues, which are fixed with a varnish so fine and exquisite that they shine like crystal, and lend a resplendent luster to the Palace as seen for a great way round. This roof is made too with such strength and solidity that it is fit to last forever.”

He was amazed by both its size – “You must know that it is the greatest Palace that ever was” and its magnificence – “The roof is very lofty, and the walls of the Palace are all covered with gold and silver. They are also adorned with representations of dragons [sculptured and gilt], beasts and birds, knights and idols, and a sundry of other subjects.”

Marco Polo’s account of the Chinese capital ignited aspirations among his fellow Europeans to explore the Middle Kingdom.

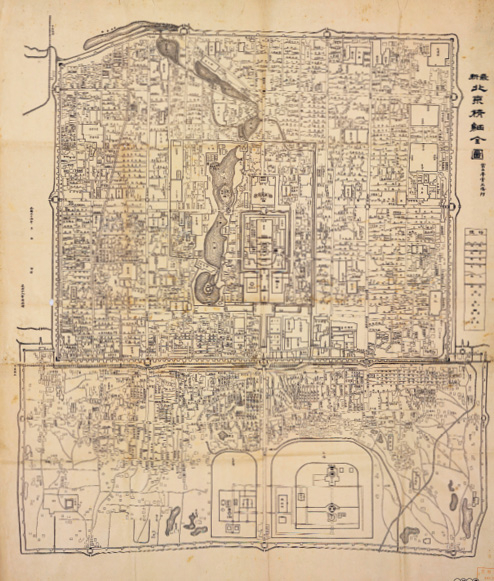

A map of Beijing dated 1908 during the reign of Qing Emperor Guangxu.

Matteo Ricci and Johannes Nieuhof

With the opening of new sailing routes over the following centuries, more Western envoys and religious missionaries came to China. On their return home, they introduced China’s political system, ethics, religions, culture, and arts to their countries of origin. This ancient civilization of the East, with unparalleled profundity and immeasurable appeal, thus became known to major Western countries at a vast array of fields to explore. Amid growing fascination about China, its capital became the focal point of Western attention.

Over the century from 1598, when Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) of Italy made his first visit to Beijing, to 1700, dozens of Jesuit priests visited the city of Beijing. Their writings about the city served as valuable sources of information for the Western world.

During his two stays in the Chinese capital, starting in 1598 and 1601 respectively, Matteo Ricci spent more than 10 years here. His manuscript during this period was later composed into The Journals of Matteo Ricci, a seminal book on Sino-European cultural exchanges during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties. It had a profound impact on European literature, science, philosophy, religion, and life. In his diary, Matteo Ricci wrote about the Central Axis of Beijing, saying that the imperial palace covers an area the shape of a narrow strip in the heart of the city, and is flanked by civic buildings on both sides. This was perhaps the earliest observation of the Central Axis by a foreigner.

In 1654 Dutch traveler and explorer Johannes Nieuhof (1618-1672) arrived in China, as the delegation secretary for Holland’s mission to the country. During his visit, he kept a travelogue and drew sketches of what he saw, which led to the later publication of An Embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces, to the Grand Tartar Cham, Emperor of China. Many European artists and architects of the 18th century used this book as a reference for their creations about the mysterious Asian country on the other side of the world. Johannes Nieuhof also took note of the Central Axis of Beijing, saying that all buildings are neatly arranged in blocks along the crossroads in the center of the city.

In a map that he drew of the imperial city, the Central Axis is clearly marked stretching across the walled Forbidden City from south to north, lined on both sides with palace buildings. It is intersected by an east-west axis in the middle, with an open space at the crossing.

This map was actually an inaccurate portrayal of the axis, as it was not based on actual site surveys, since neither Johannes Nieuhof nor other members of his delegation were allowed to walk around the imperial city. But his drawing reflects the definitive feature of Beijing – its grid layout based on the north-south Central Axis.

Stretching Backbone of Beijing City, an exhibition of various art work on the theme of the Central Axis, opens at the Capital Library of China on October 22, 2020.

Gabriel de Magalhāes

In 1648, the Portuguese Jesuit missionary Gabriel de Magalh es (1609-1677) arrived in Beijing, and spent his following 29 years in the city. His book A New History of China, which was published in 1688, depicts the Central Axis of Beijing in great detail.

es (1609-1677) arrived in Beijing, and spent his following 29 years in the city. His book A New History of China, which was published in 1688, depicts the Central Axis of Beijing in great detail.

The author described 20 palace buildings that stood in a row from south to north. After people walked through the main city gate – located between the outer imperial city wall and the southern wall, they came to a broad street which was as long as the city wall. “On the other side of this street was a rectangular square encircled by marble balustrades…The Daqing Gate was an entrance with three openings capped by three domes, on the top of which was a beautiful hall [actually a gable and hip roof]. The gate was exclusively designated for the use of the emperor when he made excursions out of the city,” Gabriel de Magalh es wrote.

es wrote.

At the northern side of the first palace building was a large courtyard framed by a 200-column colonnade on both sides called the 1,000-Step Corridor. Its breadth was twice the range of a musket, the author estimated. The courtyard straddled two gates on the Chang’an Avenue – the Eastern Gate and the Western Gate.

Despite mixing up the names of the Ming and Qing dynasties and making errors in some locations, Gabriel de Magalh es correctly portrayed the symmetrical design of the imperial city and the Forbidden City, and gave an exhaustive account of the main buildings located along the Central Axis. When Europe in the Middle Ages was plagued by political division and recurring wars, China, which covered an area of roughly the same size, maintained political stability and unity. This is why Western envoys and missionaries called Beijing the city of hope at the time. They introduced the layout of Chinese cities featuring a central axis to Europe, which exerted a lasting influence on its urban planning. As European cities are pursuing ways of modernizing their landscapes, many of them are creating their own central axes that can best represent their images.

es correctly portrayed the symmetrical design of the imperial city and the Forbidden City, and gave an exhaustive account of the main buildings located along the Central Axis. When Europe in the Middle Ages was plagued by political division and recurring wars, China, which covered an area of roughly the same size, maintained political stability and unity. This is why Western envoys and missionaries called Beijing the city of hope at the time. They introduced the layout of Chinese cities featuring a central axis to Europe, which exerted a lasting influence on its urban planning. As European cities are pursuing ways of modernizing their landscapes, many of them are creating their own central axes that can best represent their images.

WANG HONGBO is a historical research assistant with the Beijing Academy of Social Sciences