THERE is a saying among Chinese virtuosos that Longquan is the best porcelain in the south, and Yaozhou is the finest in the north. Celadon Yaozhou ware with engraved motifs is lauded as the crown jewel of North China celadon pottery.

The kiln producing Yaozhou ware was located in Huangbao Town, Tongchuan City of Shaanxi Province. Production started in the Tang Dynasty (618-907), reached its zenith in Northern Song (960-1127), and ceased during the Republic of China period (1912-1949), spanning over 1,300 years. The best known lines are celadon items with carved and impression patterns. Their translucent glaze is of greens that are neither too glaring nor too bland, and the shape is classical.

Yaozhou ware covers almost all objects of daily use, including tableware, pillows, lamps, ritual items, and toiletry articles. They come in a dazzling variety of shapes, revealing the great creativity of ancient potters. But the more prized trait of Yaozhou ware is the decoration, primarily carving, impression, and graffito. The lines are smooth but forceful and decisive, creating a relief effect. The motifs include animals, human figures, flora, and geometric drawings. With its nuanced glaze, acclaimed embossing technique and fine shape, Yaozhou ware was once unrivaled in North China.

Celadon Yaozhou Bowl with Engraved Pattern of Playing Children (Palace Museum in Beijing)

With a broad rim and circular base, the finely shaped item is engraved with an interlaced floral design and children playing games on the inside wall. Its olive-green glaze is lustrous and translucent.

Firing is critical to the ware’s sublimity. But it is merely the last leg of a meticulous 17-step process. First the raw materials are handpicked, processed and combined; and the clay is left to “decay” before being kneaded and molded. Then the glaze is applied, and the decorative pattern is added. At last the devices used to support and separate the ware in the firing process are made, and the raw ware is moved into the firing chamber. Under high temperatures the iron particles in the clay used to make Yaozhou ware turn into ginger-colored specks on its surface, a hallmark of the ware.

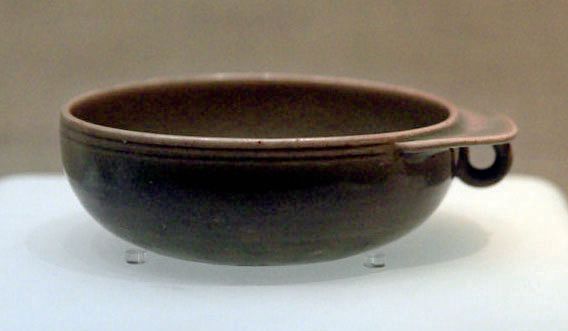

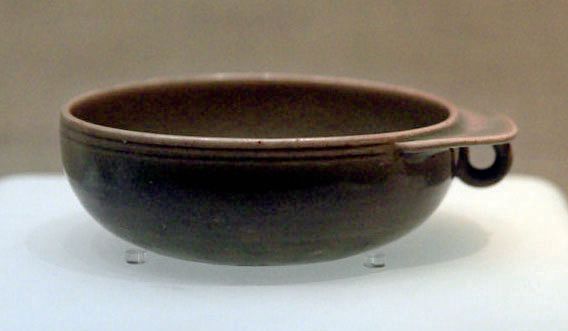

Celadon Yaozhou Ware with Pan Ear (Capital Museum, Beijing)

The Pan ear at the rim functions as a handle. Below is a ring for tying ropes. The outer wall is adorned with two parallel lines (known as string pattern) along the rim. This green-glazed ware was unearthed in a tomb from the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234) in Beijing, and the design is typical of Yaozhou ware of that period. It is a valuable reference for study of Jin pottery.

Yaozhou ware was the dominant celadon in North China during the Song Dynasty. At the peak of its production, workshops on both banks of the Qihe River (in Tongchuan City) stretching out for miles, operated day and night. The flame in their firing chambers lit up the sky at night, a spectacle lauded as one of the seven best known sights of the region. With a reputation rivaling that of the top five porcelains of the Song Dynasty, Yaozhou ware was popular among both the ruling class and average citizens, and exported to other parts of the world.

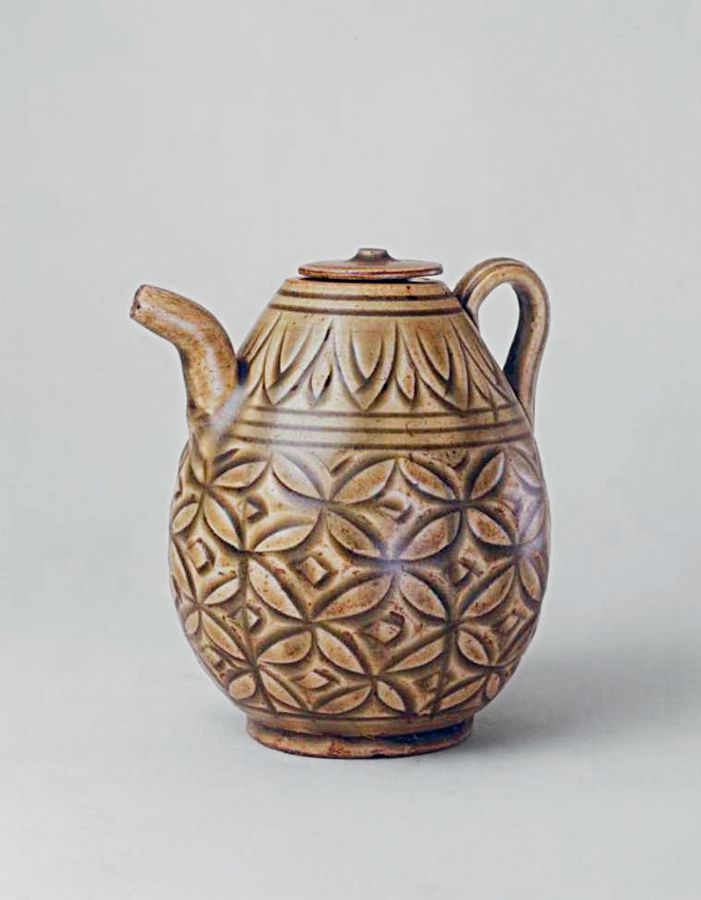

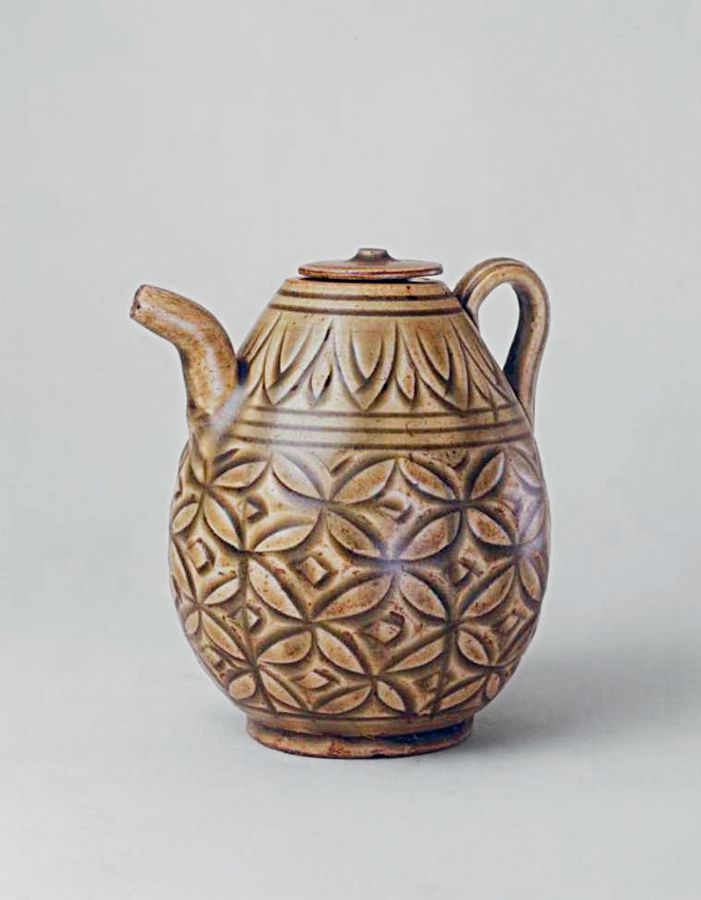

Yaozhou Kettle with Coin Design (Palace Museum in Beijing)

Covered with a small lid that has a slight protrusion on it, the piece has sliding shoulders, a bulging abdomen, circular base, and a curved spout. From top to bottom on the outside are carved a lotus flower pattern, string pattern, coin pattern, and string pattern again. The glaze is of yellowish green.

Though the kilns in Huangbao Town began to decline in the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), the site has been well preserved. In 1977 Chinese potters successfully reproduced Yaozhou ware, resuscitating the ancient art. Today it is exported to many countries in Asia and Africa, boosting cultural and economic exchanges.

SONG XIAOYAN is a course planner of antique chinaware at the Ancient Porcelain Courtyard Museum.