YUE ware is one of the most acclaimed celadons in ancient China. It was from kilns in today’s Zhejiang Province, where the first Chinese porcelain was produced in the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220) and this is why Yue ware is called the mother of Chinese porcelains.

The expertise for making Yue ware reached a peak during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), so did its production. The most loved line is that of crystal greenish glaze, a color that is often compared to green tea. In fact the fashion of drinking tea at the time had an intricate influence on the ware’s shape. In the late Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127) the Yue wares, however, fell out of favor with the emperor, and was replaced by Ru ware as the royal tributes.

The prized variety of Yue ware is Mise, meaning “a color made secretly,” celadons. The name was attributed to a poem by poet Lu Guimeng in the late Tang Dynasty, and the interpretation of the words varies. According to archives from the Song Dynasty, this product was an exclusive supply to the royal family. The recipe for its glaze and the production procedure were hence kept a secret. A Mise celadon is distinguished from a generic Yue ware for its supreme texture and luster. Celadon is a pottery term indicating wares glazed in jade green celadon color, as well as green ware and a type of transparent glaze, often with small cracks.

A Bird-Shaped Yue Cup

(Beijing Palace Museum)

The item is modeled on a bronze cup of the Han Dynasty. The bird’s head rises above the cup’s rim, with spreading wings and curved legs below. The tail stretches out at the other side of the cup as the handle. Both the inside and outside wall is covered in a greenish glaze with golden speckles and fine cracks. The cup is both a practical drinking container and an example of fine design.

In 1987 an ancient pagoda at the Famen Temple in Shaanxi Province collapsed, revealing a cellar where a hoard of invaluable items was discovered along with a catalog bearing their names and specifications. Among them are 14 Mise celadon wares offered by Tang Emperor Li Cui (833-873) to the Buddha. These are the first verified objects of the mysterious celadon that was previously only known via recorded images.

A Lotus-Shaped Mise Tea Cup on Saucer (Ningbo Museum)

Porcelain tea cups first appeared in the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317-420), having a tubular shape on a flat circular base. This item from the Tang Dynasty is a combination of a lotus-flower-shaped cup and a lotus-leaf-shaped saucer, which is believed to be evidence of the prominent Buddhism and tea culture in Ningbo more than 1,000 years ago.

The color of Mise celadon is reminiscent of a luxuriant mountain or a finely polished jade. This effect is accredited to a production procedure that is technically demanding and rigorously executed. For instance, any slight deviation in the firing process may result in a glaring difference in the glaze color. In the times before thermometers were invented it was an exacting job to maintain the heat at the desired temperature in order to produce an even glaze of lucid beryl color. The techniques to make Yue wares laid the foundation for Yaozhou and Longquan wares of later eras.

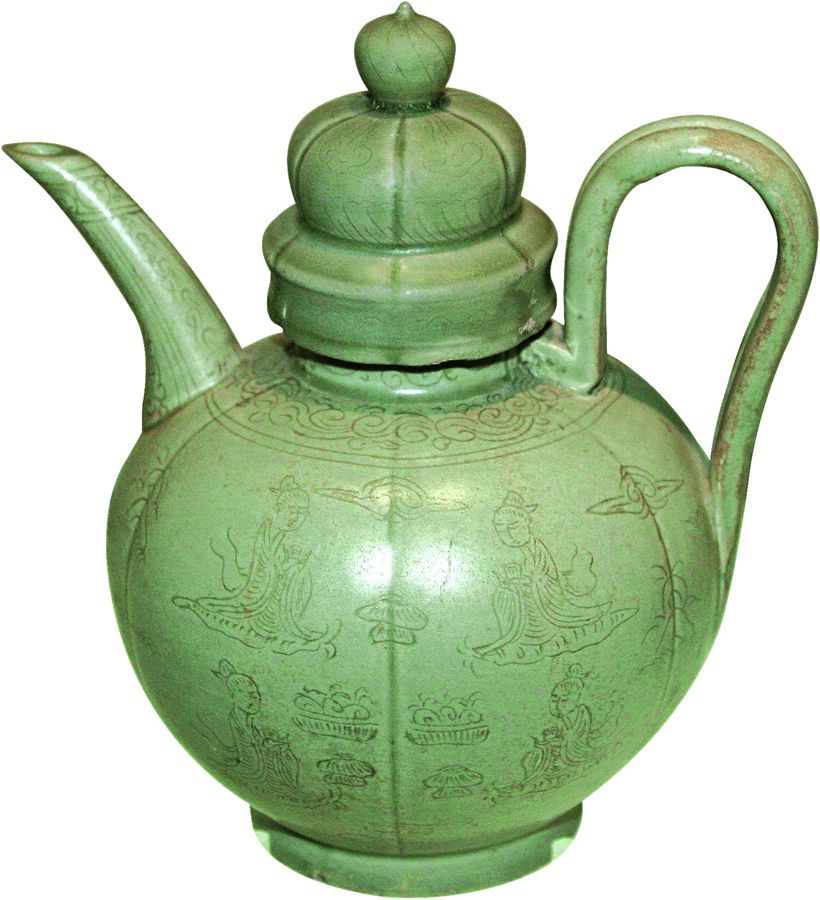

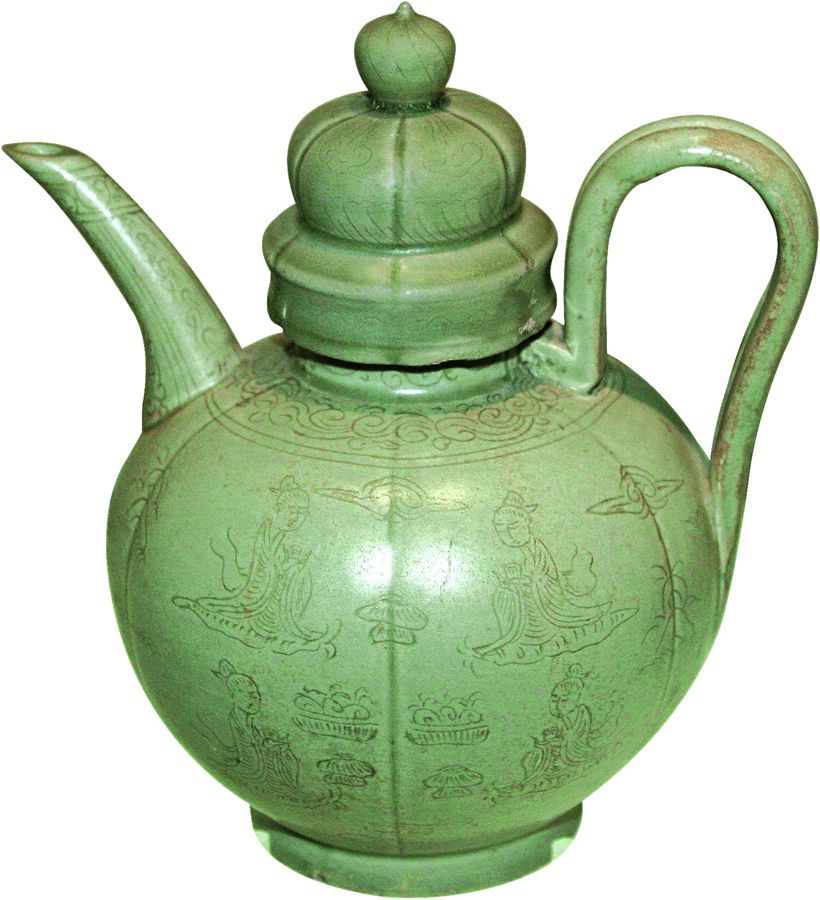

A Yue Gourd Vase with Greenish Glaze

(National Museum of China)

The globular vase is dated to the early years of the Tang Dynasty. The pronunciation of bottle gourd is similar to “fortune and promotion” in Chinese. With plentiful seeds (a homophone of sons), the plant is also a token of a blessed big family, and hence a popular motif in Chinese arts.

In addition to its ethereal glow, Yue ware stands out for its fluid shape. In its early years, in order to highlight the glaze that is as smooth and lustrous as jade, potters added minimal decorations to its surface. It was not until the late Tang Dynasty that Yue wares carved with flowers, butterflies, fish, cranes, dragons and phoenixes appeared.

For the firing, clay wares are baked directly in the firing chamber or put in a saggar, a protective casing, before entering the chamber. Either way they are separated from each other by tiny bits of clay, which explains the specks on the surface of each finished product.

The concept of an official kiln started with Yue wares, as for the first time in history a brand of chinaware was reserved for the royal family only. Its production spanned several dynasties over more than 1,000 years, and the product was a major export of the Tang Dynasty, sharing Chinese culture with the rest of the world. Yue wares have borne witness to both the extravagance of the last rulers of an unrivalled empire and the vibrancy of the marine Silk Road.

SONG XIAOYAN is a course planner of antique chinaware at the Ancient Porcelain Courtyard Museum.